In this installment of the “What Would Margaret Do” blog series, our focus will shift to the education system in America. We will also be taking a look at the importance, and subsequent removal, of religion within education; from the last installment we learned that religion within the confines of Margaret’s life had an extreme impact on the ways in which she viewed the world so to link these two thoughts together becomes increasingly seamless. As we have mentioned previously, Margaret understood that a “certain degree of wealth and education allowed a woman to take a stand against patriarchal culture, and she used those benefits to her own advantage as well as to help others politically and culturally”; for Margaret, education and schooling were not just important, but extremely valuable. As with most experiences in her life, Margaret was able to see how the educational opportunities provided to you when you are a working lower middle class family, are drastically different than the higher educational opportunities that she was able to afford to her own children. We will explore and unpack not only Margaret’s personal experiences with education and the presence in her life, but weave in the general narrative of educational reform in the 19th and 20th centuries. In stark comparison we will shed a light on the modern culture of education, and how the current administration will view, and construct, the educational future of America. In an attempt to draw a more complete picture, we invite you to continue along in our blog series that explores the socio-political instances that were prevalent in Margaret’s life, in which she had taken an extremely vocal and public stand, to help you conclude in 2017…What Would Margaret do?

In this installment of the “What Would Margaret Do” blog series, our focus will shift to the education system in America. We will also be taking a look at the importance, and subsequent removal, of religion within education; from the last installment we learned that religion within the confines of Margaret’s life had an extreme impact on the ways in which she viewed the world so to link these two thoughts together becomes increasingly seamless. As we have mentioned previously, Margaret understood that a “certain degree of wealth and education allowed a woman to take a stand against patriarchal culture, and she used those benefits to her own advantage as well as to help others politically and culturally”; for Margaret, education and schooling were not just important, but extremely valuable. As with most experiences in her life, Margaret was able to see how the educational opportunities provided to you when you are a working lower middle class family, are drastically different than the higher educational opportunities that she was able to afford to her own children. We will explore and unpack not only Margaret’s personal experiences with education and the presence in her life, but weave in the general narrative of educational reform in the 19th and 20th centuries. In stark comparison we will shed a light on the modern culture of education, and how the current administration will view, and construct, the educational future of America. In an attempt to draw a more complete picture, we invite you to continue along in our blog series that explores the socio-political instances that were prevalent in Margaret’s life, in which she had taken an extremely vocal and public stand, to help you conclude in 2017…What Would Margaret do?

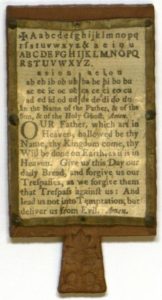

The history of education within the confines of the United States of America is one that shows a historical reliance on an educated population, being a superior population. Harkening back to the arrival of Puritans to New England in the 1700s, you see edic ts set forth to communities requiring a public parochial school system of some type, funded by the very public attending-with the crucial exception of the poorest members of the community. While this was attainable in relatively populous areas, not every town that sprang up along the eastern seaboard could afford to build a schoolhouse, hire a schoolmaster and teachers, and more importantly, be without their children at home to help with chore or farm work. Within a few short seasons, it had become common practice to have a member of the family teach the children at home, using tools such as the hornbook, a crude paddle made of horn with a sheet of the alphabet, common syllables, and most importantly, for these Puritan settlers, The Lord’s Prayer, inscribed on the reverse. These rudimentary forms of education were the bare minimum to raise a town of men who were at least in some small part, literate. Education in the 17th century relied extremely heavily on a religious education, as opposed to a tactile one, and placed a heavier reliance on the ability to recite a Christian bible verse and live a God-fearing life, as opposed to having a vital understanding of arithmetic, reading and writing.

ts set forth to communities requiring a public parochial school system of some type, funded by the very public attending-with the crucial exception of the poorest members of the community. While this was attainable in relatively populous areas, not every town that sprang up along the eastern seaboard could afford to build a schoolhouse, hire a schoolmaster and teachers, and more importantly, be without their children at home to help with chore or farm work. Within a few short seasons, it had become common practice to have a member of the family teach the children at home, using tools such as the hornbook, a crude paddle made of horn with a sheet of the alphabet, common syllables, and most importantly, for these Puritan settlers, The Lord’s Prayer, inscribed on the reverse. These rudimentary forms of education were the bare minimum to raise a town of men who were at least in some small part, literate. Education in the 17th century relied extremely heavily on a religious education, as opposed to a tactile one, and placed a heavier reliance on the ability to recite a Christian bible verse and live a God-fearing life, as opposed to having a vital understanding of arithmetic, reading and writing.

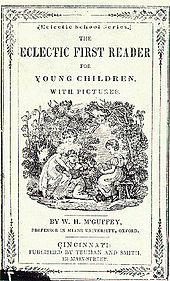

The 18th century brings along important changes in the understanding of education’s role in one’s life, as well as the topics you are being educated on. By the turn of the 18th century, there had been an increased desire to educate  the entirety of a person, rather than just the soul to be saved, and we see the rise of the Common School. In the truest sense, this was the beginning of the public school system that we acknowledge and use today. Introduced by reformer Horace Mann in the 1803s, he “proposed a system of free, universal and non-sectarian schooling. Each district would provide a school for all children, regardless of religion or social class.” These new “common schools” would focus on the reading, writing and arithmetic that had occupied education previously, however, the common schools believed in instilling “a common political and social philosophy of sound republican principles” hoping that this would allow children to gain the appropriate skills and knowledge to be a productive democratic citizen, as opposed to a servient child of god. It is around this same time that we see the advent of the McGuffey Eclectic Reader; similar to its predecessor the Hornbook, the McGuffey reader was the essential text in educating this new generation. Used as the main textbook from the mid-19th through 20th centuries, the primers would be “graded” between levels 1-6, as 6th was the typical final stage in one’s education.

the entirety of a person, rather than just the soul to be saved, and we see the rise of the Common School. In the truest sense, this was the beginning of the public school system that we acknowledge and use today. Introduced by reformer Horace Mann in the 1803s, he “proposed a system of free, universal and non-sectarian schooling. Each district would provide a school for all children, regardless of religion or social class.” These new “common schools” would focus on the reading, writing and arithmetic that had occupied education previously, however, the common schools believed in instilling “a common political and social philosophy of sound republican principles” hoping that this would allow children to gain the appropriate skills and knowledge to be a productive democratic citizen, as opposed to a servient child of god. It is around this same time that we see the advent of the McGuffey Eclectic Reader; similar to its predecessor the Hornbook, the McGuffey reader was the essential text in educating this new generation. Used as the main textbook from the mid-19th through 20th centuries, the primers would be “graded” between levels 1-6, as 6th was the typical final stage in one’s education.

Established and written by William Holmes McGuffey, the child of Scottish immigrants had a knack for memorization. Becoming a school teacher at the age of 14, McGuffey began traveling around his home state of Ohio, becoming a teacher in many of the suburban pockets throughout the state. Faced with the inconsistency between not only the ages of his students, ranging anywhere from 6-21, but also in their texts-as textbooks did not exist at the time, many that were able to be found were riddled with inaccuracies and had become outdated. McGuffey wrote his first reader in 1835, focusing primarily on phonics, identification of letters and their arrangement into words. After each chapter, the student would then practice their cursive of the new phonics and words on slate. For the first time in educational history, children were not just learning a pre-determined list of words without context; they were using word repetition with a reliance on proper pronunciation within the context of real literature to aid in the student’s concrete understanding of basic words, while gradually introducing them to new. There were no prayers to learn, or bible verses to be memorized; this was a radical change in the stagnant education system that had been in place for nearly 60 years.

By 1876, many states across the Union began passing Blaine Amendments, named after James G. Blaine, that would forbid the use of public tax dollars to fund local parochial, religious based schools, and was passed by 38 of the 50 states. By the 1890s this had become a prominent issue within the schooling system as there was an exponential increase in the numbers of Catholic immigration to the United States. This shift stemmed namely from the fact that public schools at the time were typically leading children in Protestant prayers and reading from the Protestant bible in the classroom. Because of the worry that their Catholic children were now being raised Protestant, while in a public school, many Catholics began to establish schools of their own, that focused more on their own Catholic beliefs, rather than Protestant. The United States as a whole was beginning to shift from a culture that was completely intertwined between church and state, to a realization that there should, in fact, be a separation. It is also around this same time, that the National Education Association began to recommend that children receive 12 years of schooling; by the 1890s we essentially see the public school system that we are familiar with today with regional areas setting up grammar schools, high schools, local standards, etc. By 1910 nearly 72% of American children are attending school, either publically or privately.

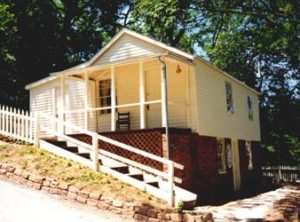

The educational story of Margaret Tobin Brown is one that is a bit unusual for a woman who came of age from the 1870s-1880s. The child of two Irish-Catholic Immigrants, John and Johanna Tobin, education was extremely valued in her hometown Hannibal, Missouri. While most children in small towns like Hannibal were expected to gain at least some schooling and then go out to earn for the family, the Tobins considered it much more important that their children receive as much schooling as possible. Being the children of working families, the advent of the free public school system, helped to relegate the responsibilities of education away from Johanna and onto a teacher, allowing Johanna to work and provide for her family with different means. Taught by their aunt, Mary O’Leary, at the neighborhood school right  across the street from the small Hannibal home she shared with her family, Margaret and her siblings would complete their studies clear through the 8th grade, and at the age of 13 would have been considered as educated as a woman could be. The passion that had been instilled in her from an extremely young age would see her pick herself up by her wills and head to work in the Garth’s tobacco factory like many young women….to bide their time until marriage, at the ripe age of 16. Margaret, never one to rest on her laurels, would see the drive for education follow her to the tops of the Rocky Mountains and come to fruition in the Queen City of the Plains.

across the street from the small Hannibal home she shared with her family, Margaret and her siblings would complete their studies clear through the 8th grade, and at the age of 13 would have been considered as educated as a woman could be. The passion that had been instilled in her from an extremely young age would see her pick herself up by her wills and head to work in the Garth’s tobacco factory like many young women….to bide their time until marriage, at the ripe age of 16. Margaret, never one to rest on her laurels, would see the drive for education follow her to the tops of the Rocky Mountains and come to fruition in the Queen City of the Plains.

After arriving in Colorado in the 1880s, and watching her husband J.J. Brown make his fortune and legacy in gold at the Little Johnny Mine in Leadville, her passion for education was reignited. Constantly looking to keep her mind not only sharp, but occupied, she was able to channel her desire of learning into her passion for travel. Believing that the best way to learn about the diverse cultures of the world was to experience it, Margaret became a learner of  languages and spoke over 6 in her lifetime. Taking it upon herself to hire tutors on various subjects for the remainder of her life, her development of a well-rounded and diverse language speaker would prove to help her out more times than not in her life. The ability to be fluent in English, French, Italian, Spanish, Russian, German, Braille and learning Greek at the end of her life, gave proof to the fact that she was on a constant mission to quench her thirst for knowledge. Her passion for education wasn’t just limited to her, now that she was a woman of means, she wanted to provide the best education possible to her very own children, Helen and Larry, as well as to the children of Denver.

languages and spoke over 6 in her lifetime. Taking it upon herself to hire tutors on various subjects for the remainder of her life, her development of a well-rounded and diverse language speaker would prove to help her out more times than not in her life. The ability to be fluent in English, French, Italian, Spanish, Russian, German, Braille and learning Greek at the end of her life, gave proof to the fact that she was on a constant mission to quench her thirst for knowledge. Her passion for education wasn’t just limited to her, now that she was a woman of means, she wanted to provide the best education possible to her very own children, Helen and Larry, as well as to the children of Denver.

As Helen and Larry grew, their names quickly began to appear within the society pages, their childhood was starkly different than that of their parents. As they were now at the mercy of their mother’s means, they would go on to receive the best education that money could buy. Their first educational experience was at a local school run by Lucy Green, eventually the school would fold and Ms. Green would move into the Brown home in order to tutor the children personally. It wouldn’t be too far of a stretch to believe that Margaret would take this opportunity to educate herself when the opportunities would present. According to Kristen Iverson, the preeminent Margaret Brown biographer, “both children attended the Sacred Heart College, a Catholic school in Denver, and eventually would be sent to boarding schools in France: Helen to the Convent of the Notre Dame and Larry to Jean D’Arc College.” Nothing but the best would be available to the Brown children, including attendance at some of the most prestigious private schools along the Eastern seaboard and boarding schools in Europe….albeit, Margaret was far more inclined to send them to Europe than J.J. was.

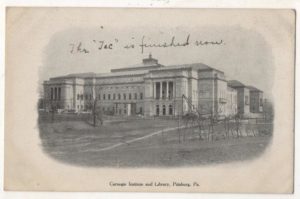

The preoccupation with education wasn’t strictly relegated to the Brown children, but Margaret used her financial ability to expand her own education. Despite having no formal education past the age of 13, being a socialite, married and with two children, she had a constant dream: attend college. As she had been increasingly traveling from Denver to New York City and Newport, she had been keeping her eyes pointed towards the development of the Carnegie Institute. By 1900, education, particularly for an adult, was an extreme privilege, with only about 5% of Americans attending university, college or a “female seminary” between 1880 and 1910. The advent of the types of university that would have been afforded to Margaret at that time were a result of the “Gilded Age Millionaires”; the men who had made their money during the industrial revolution were beginning to invest in the “future of America” by building and funding universities that would bear their name in perpetuity.

Of all of the universities that began to spring up, Margaret was drawn to the Carnegie Institute, which specifically and purposefully, supported the education of women. The Institute, founded by steelman Andrew Carnegie, believed that no matter your gender, race or socio-economic status, should have the ability to attend college and “study not only subjects related to a trade but such things as drama, literature and painting.” And with the determination that had been instilled in her from an extremely young and formidable age, Margaret was determined to become one of the institute’s first students. Margaret would spend over a year studying at the institute, thriving in the community that her wealth had afforded her to join, and it was here that she would be introduced to instruction in drama, which would have an extreme impact on the later half of her life. Her belief in mass education for all would follow her back to Denver and would be seen in the proclivity for philanthropy; she would help invest in the building and fundraising of Catholic girl’s schools throughout the city including St. Mary’s academy now located in Cherry Hills, and her work with Judge Ben Lindsey would have a reliance on education as the single largest deterrent of minor lawful disobedience while crafting their nationally renowned, and currently used, juvenile justice reform.

community that her wealth had afforded her to join, and it was here that she would be introduced to instruction in drama, which would have an extreme impact on the later half of her life. Her belief in mass education for all would follow her back to Denver and would be seen in the proclivity for philanthropy; she would help invest in the building and fundraising of Catholic girl’s schools throughout the city including St. Mary’s academy now located in Cherry Hills, and her work with Judge Ben Lindsey would have a reliance on education as the single largest deterrent of minor lawful disobedience while crafting their nationally renowned, and currently used, juvenile justice reform.

St. Mary’s Academy, school for girls was established by the Sisters of Loretto in 1864, 12 years before Colorado became a state. The Academy is one of Denver’s pioneering institutions, and is one of the only continuously running schools in the entire state. Originally located on the edge of the Prairie, in 1911 the school re-located on the same block as Margaret’s home on Pennsylvania. Margaret was an early proponent and benefactor of the school; being situated perfectly between her home and the Cathedral of Immaculate Conception up the block which she helped to fundraise for, Margaret became a regular fixture for the young women who attended the academy. Through the educational experiences that Margaret looked to bring to her children, and the educational experiences she helped to bring to the other children of Denver, we can see very clearly that having a religious tie to their education was something that seemed fairly important to her. We don’t have many records that show her support of local public, non-parochial, schools in her neighborhood, which is not to say that it didn’t happen. However, the evidence that show she was a proponent of this type of educational environment is pretty concrete.

Through the remainder of the 20th and 21st centuries, free, accessible, non-parochial, public education would become a significant bedrock to a childhood in America. With most parents believing that not only is a basic education necessary, but that the public school system in its entirety is valuable. The current administration’s Secretary of Education implemented plans to significantly change the ways in which our public school system not only function, but how varying aspects will be interpreted; for many, this caused and brought about more fear and anxiety than consolation.

DeVos’ largest, some say most controversial, beliefs about education stem, from her time as a chair of the pro-school-choice advocacy group, American Federation for Children. Believing that she acts as a beacon to “members of the movement to privatize public education by working to create programs and pass laws that require the use of public funds to pay for private school tuition in the form of vouchers and similar programs.” She is also a very large proponent of bringing the idea of a public parochial school system back to the United States, heavily promoting the use of a voucher program to be able to send tax dollars to local parochial schools by way of school-choice. This seems to come into a contradiction with the Blaine Amendments that are on the books in 35 of the United States; The local statute in the State of Colorado, Article IX Section 7 reads, “Neither the general assembly nor any county, city, town, township, school district, or other public corporation, shall ever make any appropriation, or pay from any public fund or monies whatever, anything in aid of any church or sectarian society, or for any sectarian purpose, or to help support any school, academy, seminary, college, university or other literary or scientific institution, controlled by any church or sectarian denomination whatsoever.” Most states will see a large amount of support to these various amendments within their independent state constitutions, however, in recent years with the advent of the school voucher program, many have started to claim that these types of acts are actually discriminatory, and may infringe upon the first amendment, but that’s a different discussion for a different day. Critics of these types of statutes, such as Sec. of Education DeVos, believe that as a parent they should be able to make the decisions that they feel are right for their children. If that decision comes down to removing their tax dollars from a local, public, non-parochial school, that they should be able to place those tax dollars into a school that they believe would support their children better, even if they are religiously founded and supported. In layman’s terms, “a state’s Blaine Amendment could prohibit a parent from using a state-issued voucher to pay tuition at a school that’s religiously affiliated, even if that school is academically strong and otherwise suitable to the parent’s child.”

So, the question remains, What Would Margaret Do? In a socio-political climate that seems to have us reverting back to the religiously based, privately funded, school system of the past, despite Americans deeply rooted belief in equal, non-religious “education for all”, where would Margaret stand on the issue? Some would suggest that she may in fact be a supporter of DeVos’, after all, the Browns were the epitome of parents using school choice to advance the education of their own children, not to mention how her own Catholicism was revered within her family. Helen and Larry had consistently been bounced from school to school and tutor to tutor, in order for them to receive the best education possible; Were they only able to receive their education in that way because they were the children of wealthy parents? To the point made earlier, Margaret and J.J. had more than enough money to send their children absolutely anywhere, including the public school in their neighborhood over at Denver East, however, chose to send their children to private and even international schools, most of which tended to place high regard to intertwining Catholic ideology into their education. If a charter school system were available would they have used it, despite them already having the means to devote to their children’s personal education? To play the Devil’s Advocate, we also know that Margaret is a staunch believer in your position not dictating your life, and that you are able to rise above any preconceived notions about your ability to accomplish outside of your race, gender, ethnicity and financial background. She herself was able to garner the education level that she did because of the public school system that was heralded by Horace Mann in the 1830s. In the words of her famous Hannibal neighbor, Mark Twain, Margaret never seemed to allow her schooling to affect her education and of the world and the community in which she found herself.

So I ask, from your scope and knowledge of her motivations and passions, and her interactions with our education system, both in her personal education and that of her children, coupled with her faith, What Would Margaret Do?

Written by Savannah R. Reeves

Education Programs Associate