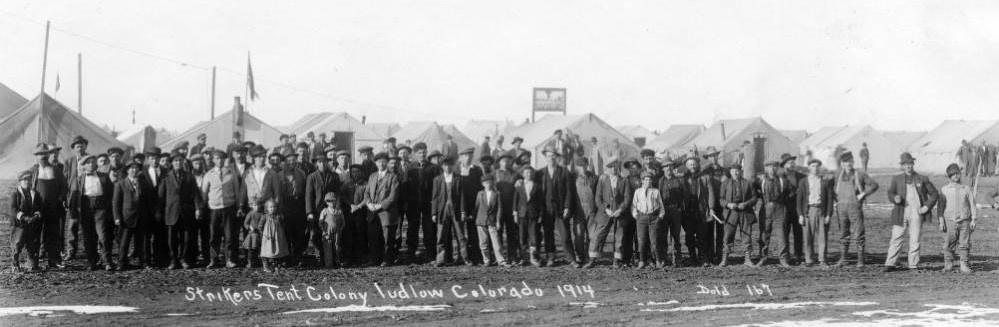

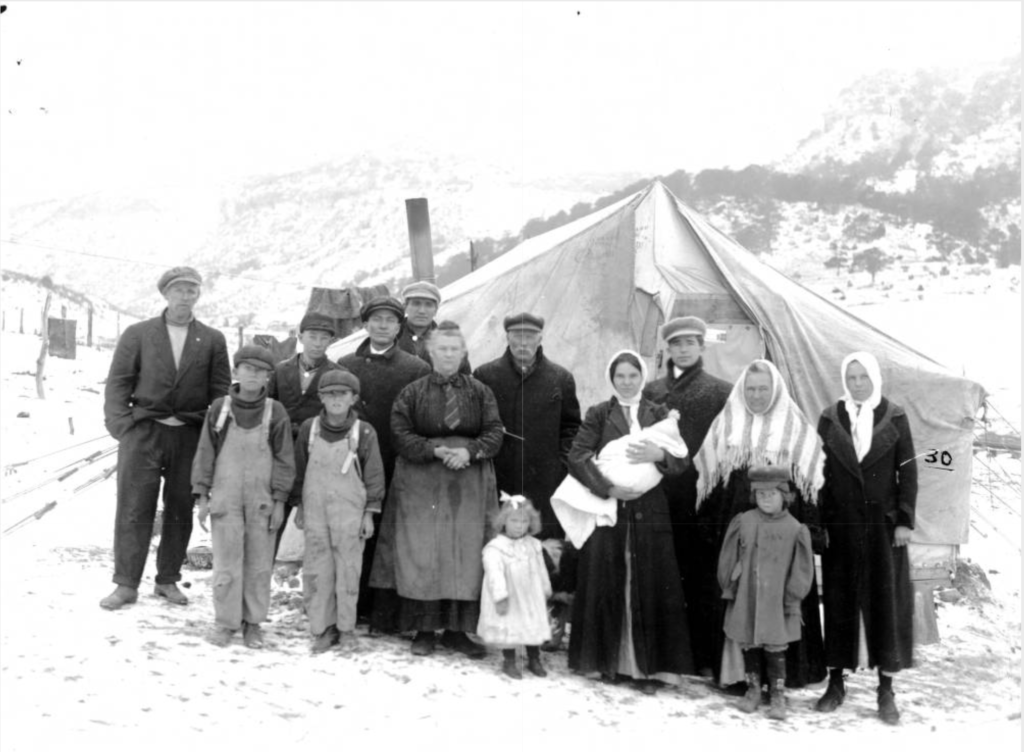

On April 20, 1914, violence broke out in Ludlow, Colorado as miners on strike were fired upon by the Colorado National Guard and the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. The event came on the heels of months of contention between the two sides. Since the beginning of 1914, miners in Ludlow had been on strike in an attempt to be granted more rights. The massacre resulted in the deaths of over 20 people and the displacement of hundreds more. This event became a defining moment in the fight for the rights of laborers, and many women took part in championing such a cause and bringing about widespread attention. One such woman was Margaret “Molly” Brown. As a dedicated philanthropist, an activist for human rights, the wife of a mine worker, and a woman with a flair for the dramatic, Margaret was uniquely equipped to offer her skills and experience to those impacted by the Ludlow Massacre. A cacophony of issues rose in the aftermath of the massacre, many of which Brown personally gave her service to; families were left homeless, jobless, and lacking necessary resources to move forward.

Striking coal miners and their families pose near Joe Zanetell’s tent. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

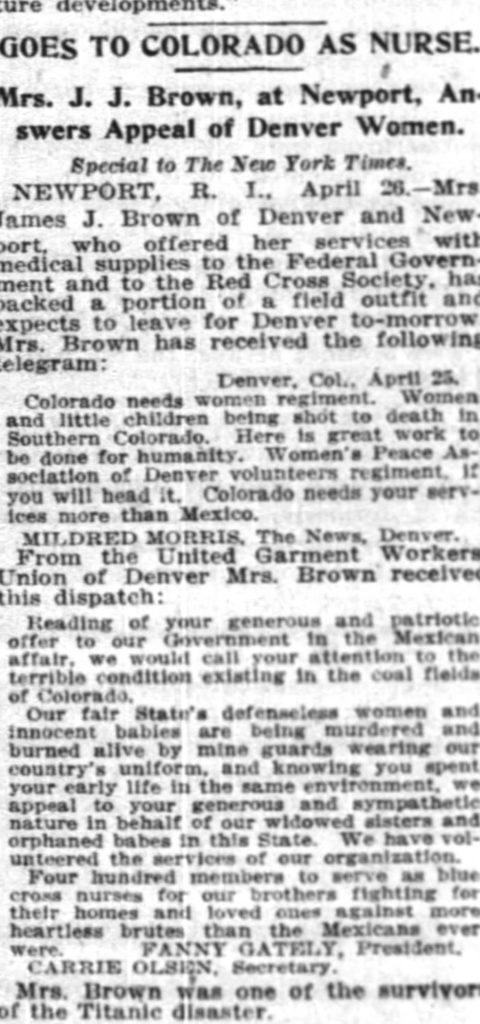

Prior to Ludlow, Margaret had already dedicated decades of her life to public service. She was well versed in the organization and execution of a myriad of philanthropic events, and had experience working directly with survivors of a traumatic event. While living in Leadville, Margaret spent her time working in soup kitchens and when her family made the move to Denver, she quickly took on many philanthropic causes such as St. Joseph’s Hospital, the Juvenile court, and many more. One newspaper called Margaret the “patron of all of the charities in the city.” She was frequently willing to lend her money and services to any cause that she was passionate about. Of course, Margaret is especially famous for her heroic acts amidst the sinking of the Titanic as she helped other women into Lifeboat Six, and took care of the survivors once they were all safely aboard the Carpathia. In fact, Margaret was actually about to leave with a regiment of soldiers to give aid to the Mexican Revolution when she heard about Ludlow and decided to lend her services much closer to home.

From The New York Times April 27, 1914.

Upon her arrival, Margaret’s main concerns included bringing peace, provision, and medical assistance to those in need. She established a Blue Cross Nurse Corps at the site of the massacre, donated a considerable amount of her own money, and partnered with Garment Workers’ Union and the Women’s Relief Association to provide necessary resources such as shoes and clothing. Margaret was also a remarkably well-educated woman for her time, and among other things she had spent time studying theater and drama in Leadville, Denver, and even at the Carnegie institute. She put these skills to good use when she organized a vaudeville benefit performance to raise money for those impacted at Ludlow.

Margaret was also able to uniquely understand both sides of the conflict in ways that many others could not. She was a woman who had not grown up with an expanse of wealth, and had been accustomed to working from a young age. Her marriage to J.J. Brown did not initially bring wealth either, as he was equally as poor as she. J.J. had years of experience working in mines, and for the first six years of their marriage, Margaret lived the life of a miner’s wife. It wasn’t until 1892 when gold was found in the Little Johnny mine, which J.J. co-owned, that the Browns began to acquire substantial wealth.

As a result, she was well informed of what miners and their families had to endure on a daily basis. Through J.J.’s involvement with the Ibex Mining Company, she was also able to experience the life of a wealthy mine operator. Brown was able to understand the views of both the strikers and the operators, and initially remained neutral in her opinion on the massacre, “I am interested in humanity and will do my duty impartially and conscientiously” However, upon seeing the devastating aftermath of the massacre firsthand, Brown quickly aligned herself with the striking miners, and made great efforts to spread the word and further their cause.

As a well-educated activist, Margaret quickly saw that the events at Ludlow were indicative of much larger issues. Like many others, she understood that Ludlow represented one small piece of the nation-wide issue of labor rights, “the recent trouble in Colorado was not by any means an affair of an individual state but was of nation-wide importance as the conditions were the same wherever a mine was in operation.” In an address she made to an audience at the Women’s Suffrage Headquarters, Brown details the poor working and living conditions that the miners and their families were forced to endure. These included unsafe and unclean mining sites, workers who were not properly trained nor adequately paid, a lack of schooling for the miners’ children, and an unwillingness on the part of the corporations to hear and acknowledge their complaints.

Margaret’s proposed solution to such injustices was the establishment of universal suffrage, which would grant everyone, including women, the right to vote. Women’s suffrage and equality was a cause which she was deeply passionate about, and the events at Ludlow only helped to strengthen her opinion on the matter. The sum of her efforts in Ludlow did not go unnoticed, and many in Colorado believed that their “mine angel” should run for congress. Though she never did make it to Congress, Margaret continued to lead a life of service after Ludlow.

By no means was Margaret alone in her efforts in Ludlow. Many women such as Mother Jones and Dora Phelps Buell also rose to prominence as a result of the works they did amidst the striking. Mother Jones was a passionate supporter of the strike. She rallied many of the men, begging them to fight for the rights they deserved. She was willing to take the fight as far as was necessary in order to see improved living and working conditions. Dora Phelps Buell played a different role in the aftermath of the strike than that of Mother Jones. She, like Margaret, was primarily concerned with ending the fighting and caring for those in need. She organized a march in Denver with over a thousand woman, hoping to gain the attention of Governor Ammons in hopes that he would call in aid to calm the violence. One article in the Denver Times explained that, “where men had failed, they [the women] had succeeded.” Women of Colorado were instrumental in bringing peace, and ultimately expanded rights to the miners in Ludlow and across the country.

One would be hard pressed to find another woman who was better positioned than Margaret to aid in the wake of the massacre. She was able to sympathize with the miners and understand their cause, while also being in the unique position of being able to provide tangible support and raise awareness of the larger issues at hand. She generously used her fame and fortune to bring a voice to the voiceless, and spur on real change.

By: Hannah Bachus, Museum Intern