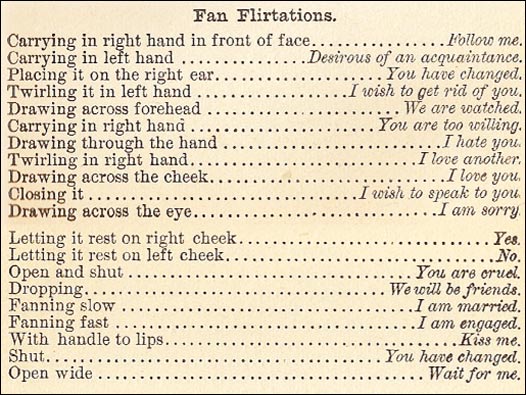

In Henry J. Wheman’s how-to guide The Mystery of Love, Courtship and Marriage Explained, advice on various activities are presented for men and women alike such as “Pet names,” “Wooing,” “How a lady should manage her Beau to make him propose Marriage,” “Twenty Ways of Popping the Question,” “The Etiquette of Engagement,” “General Remarks to Correspondence” and “Advice to the Newly Married.” One of the most interesting subjects of this guide imparts the wisdom of using everyday objects as a means of signaling messages to your current or future beloved.

The history of flirtation using everyday objects can be traced back to the Augustan Roman poet Ovid, who was known, in part, for his poetry teaching about the arts of seduction and love. In Amores 1.4, Ovid directs his married girlfriend in the discreet ways of flirting using eyebrows, wine, hand signals, and jewelry:

Watch me and my nods and my expressive features:

Catch my furtive signs and you yourself return them.

Words that are spoken without voice, I shall speak with my eyebrows;

You will understand the words traced by my fingers, words written in wine.

When the wantonness of our love comes into your mind,

With tender thumb touch your blushing cheeks;

If you shall complain about me in the silence of your mind,

Your soft hand should hang from the end of your ear;

My dear light, when I do or say things which please you,

Turn your ring round and round your fingers;

Touch the table with your hand, as men in prayer do,

When you pray for many sufferings upon you deserving husband.

The belief that the fan was employed in society to express various feelings or commands dates back to at least the early 18th century. In 1711, The Spectator, a daily newspaper written by Joseph Addison published “to enliven morality with wit, and to temper wit with morality” printed a satirical article concerning the use of fans.

‘Mr. Spectator – Women are armed with fans as men with swords and sometimes do more execution with them … The ladies who carry fans under me are drawn up twice a-day in my great hall where they are instructed in the use of their arms and exercised by the following words of command: Handle your fans, Unfurl your fans, Discharge your fans, Ground your fans, Recover your fans, Flutter your fan.

Emotions are also added to the movement of fans: “There is an infinite variety of motions to be made use of in the flutter of a fan. There is the angry flutter, the modish flutter, the timorous flutter, the confused flutter, the merry flutter, and the amorous flutter.”

Furthermore, Addison also makes the connection between the character of the bearer with the actions of the fan saying, “I need not add, that a fan is either a prude or coquette according to the nature of the person who bears it.”

The relationship between the fan and a coded language or flirtation continued later with the printing of the “Fanology or Ladies Conversation Fan” in 1797. This fan, which was designed by Charles Francis Badini, included lettered inscriptions and explanations of how to communicate in code. One example contains “Directions for the Conversation of fan” on the obverse with “Familiar Questions with their respective answers” on the reverse. The directions begin by saying that eight different motions are all that are needed to impart the whole alphabet. The position of the fan to various parts of the face indicates which number is being referred to and each number is related to a different letter to create a coded language.

In the early 1800s, the fan was losing popularity as a fashion accessory but it was soon brought back into fashion due to its use in a single dance at the ball given by the duchess de Barry at the Tuileries in 1829. The French fan maker Duvelleroy, the official fan supplier to Queen Victoria, published a leaflet explaining the language of fans to the masses in England. Some have speculated this was done in attempt to boost fan sales instead of actually imparting some secret language.

Victorian society was very concerned with proper etiquette between men and women. Advice books and columns of the late 19th century equated the clothing and accessories of a Victorian woman with her inner character. In this same vein, opening and closing a fan or hiding one’s face behind a fan was a reflection of an inner communication to a beau. In the restrictive rules of courtship in Victorian era, the fan could act as a modest tool for a woman who was attempting to catch a husband and avoid spinsterhood without engaging in more overt behavior that would label her as a coquette or as wanton.

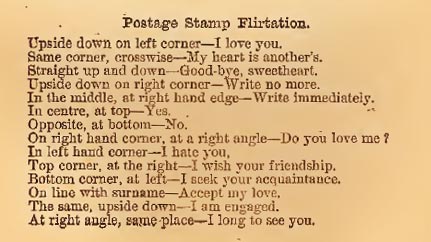

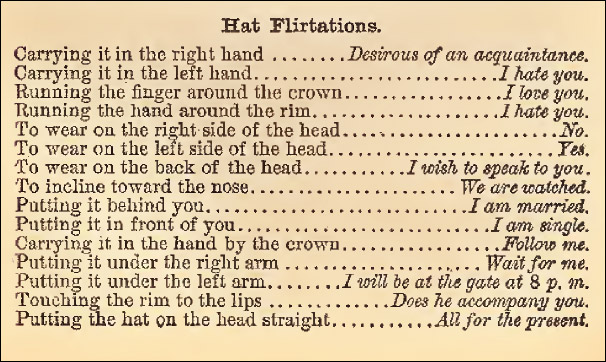

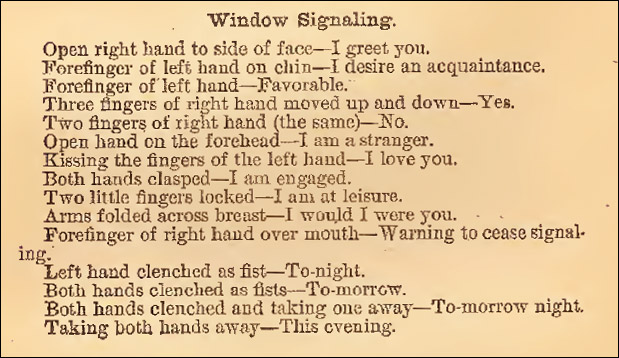

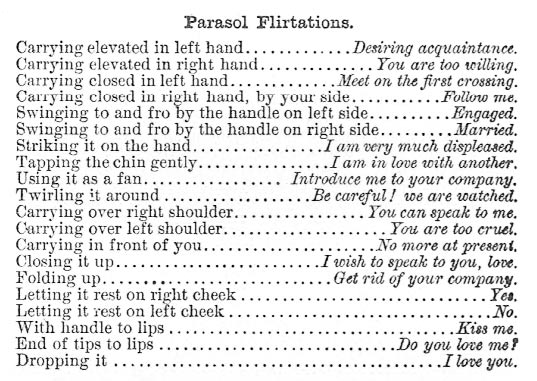

Many Victorian publications, including Cassells’ Family Magazine, expanded the language of flirtation onto other everyday objects. Secret messages could be imparted by gloves, parasols, handkerchiefs, dining table napkins, windows or even postage stamps.

The Mystery of Love, Courtship and Marriage Explained says, “Fans and flowers have each their language and why not handkerchiefs? No reason having been discovered, it has transpired that handkerchief flirtations are rapidly coming into fashion. As yet the code of signals is confined to a select few, but we do not intend that they shall enjoy the monopoly any longer, and accordingly publish a key.”

There are limits to when this communication may be employed including at the opera, theater, balls and such places but never in church. But as the book says, “we hope this restriction will be observed and are quite sure that it won’t.”

The Victorian man or woman would need to be well-versed in the specific language of all of these objects in order to not give the wrong signal to their intended flirt. Dropping your handkerchief or fan means “We will be friends,” but dropping your parasol means “I love you.” Tapping the chin with a glove or a parasol means “I love another.” but placing your forefinger of your left hand on your chin while sitting in the window means “I desire an acquaintance.”

Although the motions change due to the object, the messages being conveyed remain the same. The wielder can ask to become acquainted. They can ask the receiver to follow or wait, tell them that they are already engaged or married. They can profess their love or their hatred and ask for a kiss or ask them to go away.

Whether or not these items were actually used as a secret language, it is clear that authors and readers alike enjoyed publishing and reading the about the possibilities of using these everyday items as a means of flirtation. Below are the keys for your use and edification. Flirt wisely!

–Jen Kindick, Museum Education Specialist

Sources:

Addison, J. (1837) The Works of Joseph Addison, Vol 1. New York: Harper and Brothers.

Beaujot, A. (2012) Victorian Fashion Accessories. London: Berg.

Duvelleroy House. Duvelleroy Eventalliste 1827. [E-Reader] https://en.calameo.com/books/004031713395b2c6f5063

Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Fanology of the Ladies Conversation Fan. Retrieved from https://www.mfa.org/collections/object/fanology-or-the-ladies-conversation-fan-123930

Ovid. Amores 1.4. Translated by Wikisource. (February 2014) Retrieved from https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:Amores/1.4

Starp, A. (2018, April) The Secret Language of Fans. Retrieved from https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/the-secret-language-of-fans

Wheman, H. (1890) The Mystery of Love, Courtship and Marriage Explained. New York: Wheman Brothers.