THE GLOBE TROTTERESSES

Claiming the World

As Victorian women began looking towards the larger world, they also demanded to be recognized in the arts and sciences. Traveling in the 1900s was a man’s pursuit and women were not admitted to the professional and academic organizations that funded travel expeditions. London’s prestigious Royal Geographical Society stated, “The professional female globetrotter is one of the horrors of the latter end of the 19th century.” Despite this, women travelers contributed as much or more to the fields of anthropology, botany and ethnography than many of their male contemporaries.

Pioneering in a foreign land allowed women to have an authoritative voice in an era when few women had careers outside the home. Women contributed substantially to the fields of natural history, cultural anthropology, botany, museum collecting and medicine.

As Britain and other western countries colonized the world, male explorers were funded by geographical societies and focused their time on mapping newly acquired territories. Women, on the other hand were observing and collecting information about people, plants and animals, contributing greatly to the understanding of such regions before they were changed by outside influences. Because their expeditions were not funded by the geographic societies, women relied on indigenous people to help them survive; this intimate contact enabled women to record cultural and social information, creating the foundation for the field of social anthropology.

Women found that museums would pay for the natural and cultural specimens they collected. Travel writing and lecturing also helped women provide for themselves and support the freedoms they enjoyed while traveling. Eventually women like Isabella Bird and Mary Kingsley were recognized for their geographic accomplishments and gained membership to the Royal Geographic Society.

Here are four women that claimed the world through their travels and explorations of North American, Africa and Asia:

Mary Kingsley 1862 -1900

“We each recognized we belonged to that same section of the human race with whom it is better to drink than to fight.” –Mary Kingsley of the Fang Tribe she studied in Africa

Mary Kingsley believed that courage and integrity could help her through any situation. Once a sickly spinster with no formal education, Mary became known for her courage, intelligence, charm and humor and was the 19th century’s foremost expert on West Africa.

Born in Victorian England, Mary had a very sad childhood spent caring for her ailing mother. In order to escape the monotony of her life she would sneak away to her father’s study and read books on travel. At the age of 30, after both her parents had died, she decided to make those stories a reality and headed off to see the Africa of her imagination.

On African soil

During her journey, Mary found that she was no longer sick; she also found a love of nature and the keen sense of humor for which she became famous. Her travel books and lectures are some of the wittiest and most entertaining ever written.

Mary led solo expeditions into the Congo region of Africa in 1893 and in 1895. She collected fish, insects and reptile specimens for the British Museum in London. She also recorded native religious beliefs while collecting scared objects, called fetishes. During her expeditions, she traveled as a trader, believing it was the best way to collect the “fish and fetish” that she was after and gain the confidence of the local tribes she was studying.

Mary Kingsley’s Canoe on the Ogowe River in Gabon 1896

Because she did not have a lot of money to travel, Mary relied on the Fang Tribe, notorious cannibals, to help her survive. One evening while staying as a guest of the Fang, “she was bothered by a terrible smell. She tracked it to a small bag that was hanging from the roof. She carefully emptied the bag into her hat when she realized that the Fangs really were cannibals after all. The contents were a human hand, 3 big toes, 4 eyes, 2 ears. The hand was fresh, the others only so so, and shriveled.” Still, Mary had the courage to go on with her collecting.

Mary published two books about her African travels. She was a very amusing story-teller, entertaining audiences of over two thousand people with tales about how she traded her extra blouse to a disgruntled tribesman and how ridiculous he appeared dressed in her silk blouse and nothing else.

Isabella Bird 1831 – 1904

A Sickly Spinster Turned Spirited Adventuress

Isabella Bird was the most dramatic of the Victorian women travelers. She was controversial, emotional and exasperating, with phenomenal energy and failing health. She preferred to travel light and on her own, her only supplies being tea, dried soup and saccharine. She compared her dangerous adventures to the feeling of falling in love. She was the first woman to ever address the Royal Geographical Society, who deemed her “the most accomplished traveler of her time.”

Born in England to a middle-class family, Isabella suffered from poor health and spinal problems. At age 18, she had a tumor removed from her spine and spent the next years of her life in bed. Finally, doctors recommended traveling to help relieve her pain.

Once on foreign soil, Isabella blossomed. She began to do things she never thought she would be able to do. Her first trip was to the United States. The lively and colorful letters she sent to her family resulted in her first book, The English Woman in America, published in 1856.

Riding Astride

However, when Isabella returned home she became ill again and after her parents’ death she departed for the Sandwich Islands, now Hawaii. In Hawaii, she noticed that the Hawaiian women did not ride a horse side-saddle but rode astride as men did. After trying this method, Isabella found her back pain gone. From that moment she never rode side-saddle again.

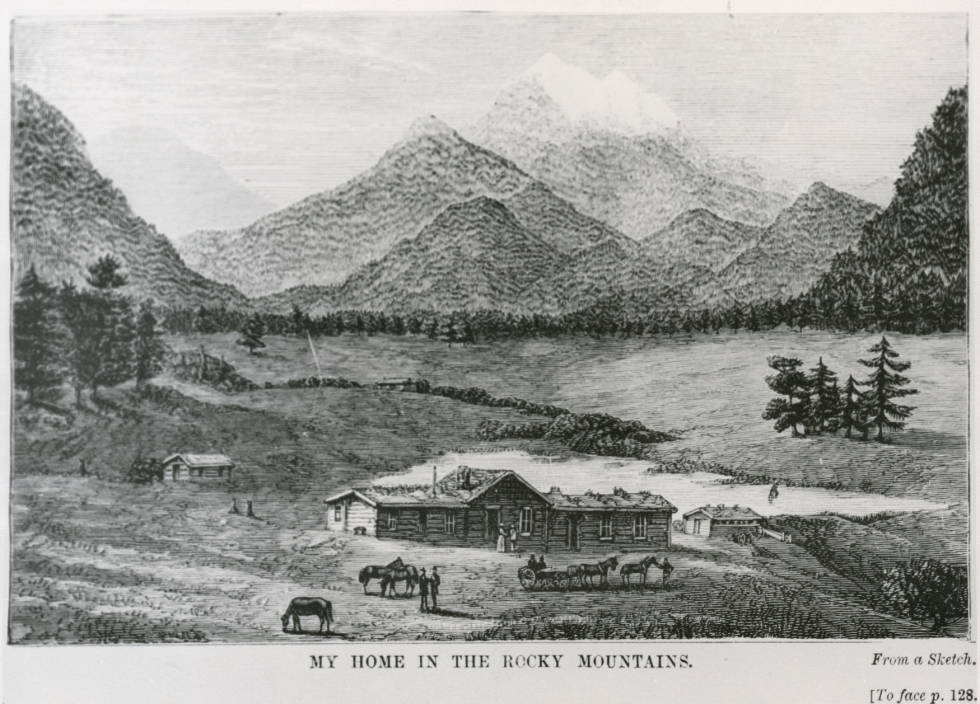

Colorado’s Rocky Mountains Captured Isabella’s Heart and Soul

In the United States, Isabella traveled alone by horseback to the Rocky Mountains. She visited mining camps and ranches, learned to drive wagons and herd cattle. She hiked 14,000 foot peaks in Estes Park and was snow-trapped in a mountain cabin for the winter. Her love of the Rocky Mountains inspired her to publish A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains in 1879. The book became enormously popular.

Isabella spent her remaining years traveling through Asia searching for the most remote villages and temples. She took pride in the fact that she ventured where few had gone before. Her travels resulted in many books that colorfully described daily life in exotic places. She described meals, accommodations, politics, economics and the costume and character of the people she visited. She became known as a serious geographer whose reports on distant cultures contained hard facts in addition to entertaining anecdotes. Her life’s work was finally recognized in 1892 by the Royal Geographical Society when they invited her to speak at a meeting. That same year the group voted to allow her membership into the elite club.

The Golden Chersonese and the way thither 1883

Isabella Bird made her way through the continent of Asia, staying with local villagers and observing their shrines and religious ceremonies. She rode elephants through muddy rivers and describes her harrowing account of being submerged to her neck in water simply as “this mode of ridding is not comfortable.”

Marianne North 1830 – 1890

Reveling in Freedom and Solitude

A quiet and subdued woman, Marianne North traveled the world intricately painting specimens of tropical plants in their natural setting. All of her work is of amazingly high quality and all was painted in extreme conditions. What is most amazing about her accomplishments is the number of specimens she was able to paint in her lifetime. In the end she completed 832 oil paintings of over 1000 specimens.

Considered the most “normal” of the lady travelers, Marianne North came from a cultured background and had plenty of money to fund her travels. She had become bored with life at home and craved the instability of hard traveling. Nothing seemed to faze her except cold weather which she said “shriveled her up, made her head and teeth ache and brought on the return of her old pain.”

Grand Volcanoes and Colorful Markets

Marianne’s journeys led her to Jamaica, the Untied States, Brazil and Japan. She also traveled to Indonesia and stopped on the island of Java, where she was enamored with the grand volcanoes and colorful markets. She wandered through the jungles of Ceylon and lived alone in India, traveling south to admire the temples and then north to the Himalayan foot hills. In Australia, she was fascinated with gum trees and koalas. In her elder years she visited Hawaii and finally set foot in Africa and Chile to finish her collection.

As the number of her paining grew, Marianne sent them to be exhibited at the Kew Gallery in the Royal Botanic Gardens in London. She eventually paid for a gallery to be built at the Kew where her paintings could be on permanent display. They still hang there today.

Freya Stark: 1893 – 1993

The Quintessential Explorer

Freya Stark explored the uncharted places on the maps of the Middle East. Freya fell in love with the desert and spent her days following treasure maps, digging for archaeological ruins and helping British intelligence agents during WWI. She wrote fourteen extremely insightful travel books on history and exploration, focusing on life in Persia, Arabia and Turkey.

Believing that all travel to new places was a form of personal exploration; her accounts were inspiring, poetic and witty. Typical of other women travelers, Freya suffered many ailments including the measles, heart attacks, malaria and dengue fever but she refused to let them slow her down.

Born into a non-traditional English family that traveled all over Europe, Freya had a nomadic childhood. While in school in Italy she sought out a monk who could teach her the Arabic language, believing that “the most interesting things in the world were likely to happen in the neighborhood of oil.”

THE WILD AND OPEN WORLD

At the age of 34, Freya departed on her first trip to the Middle East, stopping first in Lebanon and then Syria where she became entranced with the dessert. She loved the peaceful pleasures of camping and wrote “I was happy to be out in the wild and open world, with night and the long unaccustomed slight spice of danger.”

By 1929, Freya had moved to Baghdad where she lived with an Arab shoemaker and his family, far from the British section of town. Because of this, people suspected she was a spy.

Freya funded her travels by turning her experiences into books. She enjoyed sitting and chatting with local people. She used stories to add life to her writing, weaving history with the specifics of day-to-day life. It is certainly her sense of wonder that made her writing inspiring. She was also a lecturer on the art of travel, amusing her audiences with comments such as “I used to walk on ahead of my miserable guide, because even a bandit would stop and ask questions before shooting when he saw a European woman strolling on alone, hatless.”

By: Jen Kindick, Museum Education Specialist