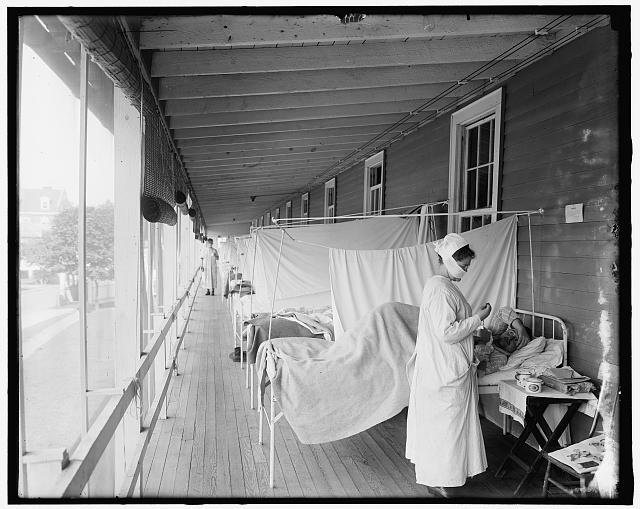

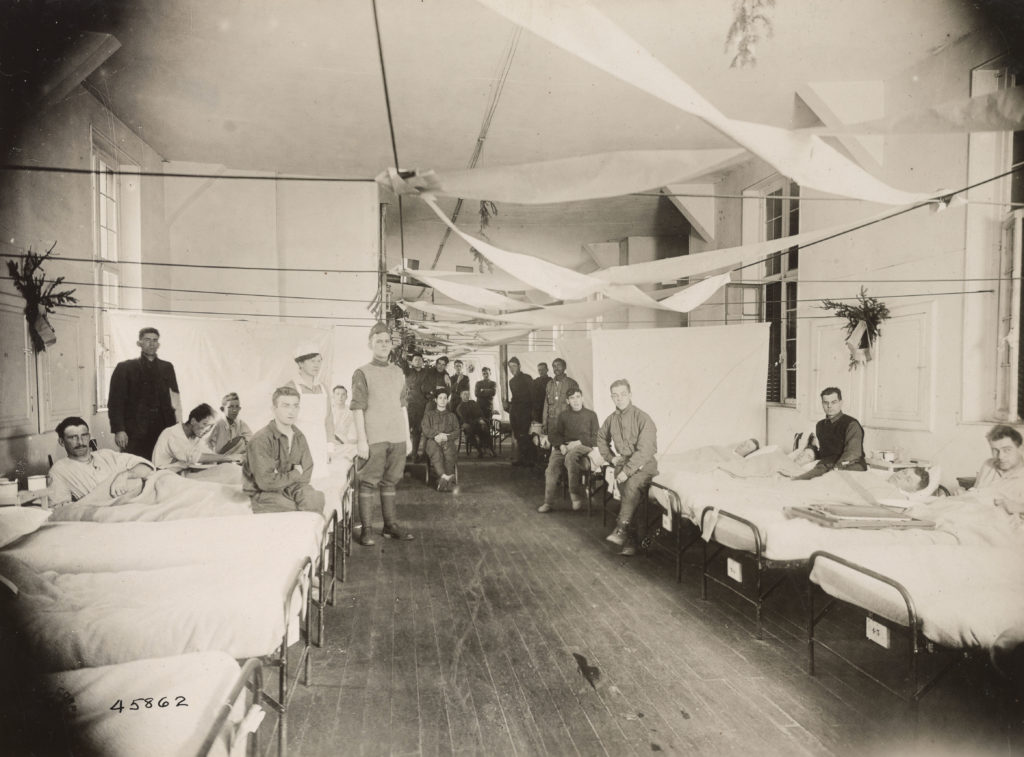

Walter Reed Hospital Flu Ward [1910-1920]. Courtesy of Library of Congress

It begins with a headache and tiredness followed by a dry, hacking cough. Loss of appetite and stomach problems develop; on the second day, excessive sweating. The symptoms are so severe that it is misdiagnosed at first as cholera, typhoid and dengue. The majority of deaths are caused by secondary infections like bacterial pneumonia, hemorrhages and edema of the lungs, which develop as a result of the flu combined with malnourishment, poor hygiene and overcrowded conditions. The disease is virulent and fast. Those healthy at breakfast could be dead by the evening.

From 1918-1920, the Spanish influenza pandemic circled the globe. With a mortality rate around 2.5%, between 20 and 40 million people died worldwide, including about 657,000 Americans. The pandemic was so severe that the average lifespan in the United States was depressed by 10 years. Unlike other flus that had come before where the victims were mostly the very young and very old, the mortality rate for the Spanish flu young healthy people was unprecedentedly high. In fact, those populations aged 15-44, particularly 25-34, were the most susceptible to dying.

In 1918, World War I was ending. One year after the United States entered the war, the Armistice was declared on November 11, 1918 and the Treaty of Versailles, officially ending the war, was signed seven months later. Before the end was in sight, French and American troops had begun to be affected by a benign influenza as early as April of 1918. By the summer, the virus had become extremely virulent.

By the fall of 1918, the influenza made its first appearance in Colorado. On September 21 of the same year, 12 soldiers from Montana who were training at the University of Colorado, Boulder fell ill. Within a week, the number of cases of influenza on campus had increased to 95. Fraternity houses became makeshift hospitals and convalescent wards. M.E. Miles, chief public health officer and doctor, ordered a city-wide quarantine as the epidemic took hold of Boulder. All schools and the university were closed. Every day the campus newspaper, the Daily Camera, posted the names and addresses of those people who had become sick with the flu.

On September 27, Blanche Kennedy, a young Denver University student died of pneumonia after returning from a trip to Chicago. This was Denver’s first influenza related death. Dr. William H Sharpley, the Manager of Health and Charity, took action in Denver. He had proactively formed an influenza board on September 26 after receiving reports from Boulder and other parts of the state about the spread of the influenza. He urged social distancing and other preventative measures such as covering coughs and sneezes and keeping homes and offices well-ventilated. Other less helpful recommendations included: Remember the 3 C’s “Clean mouth, clean heart, and clean clothes”; “Avoid tight clothes and shoes”; and “Food will win the war- chew yours well”.

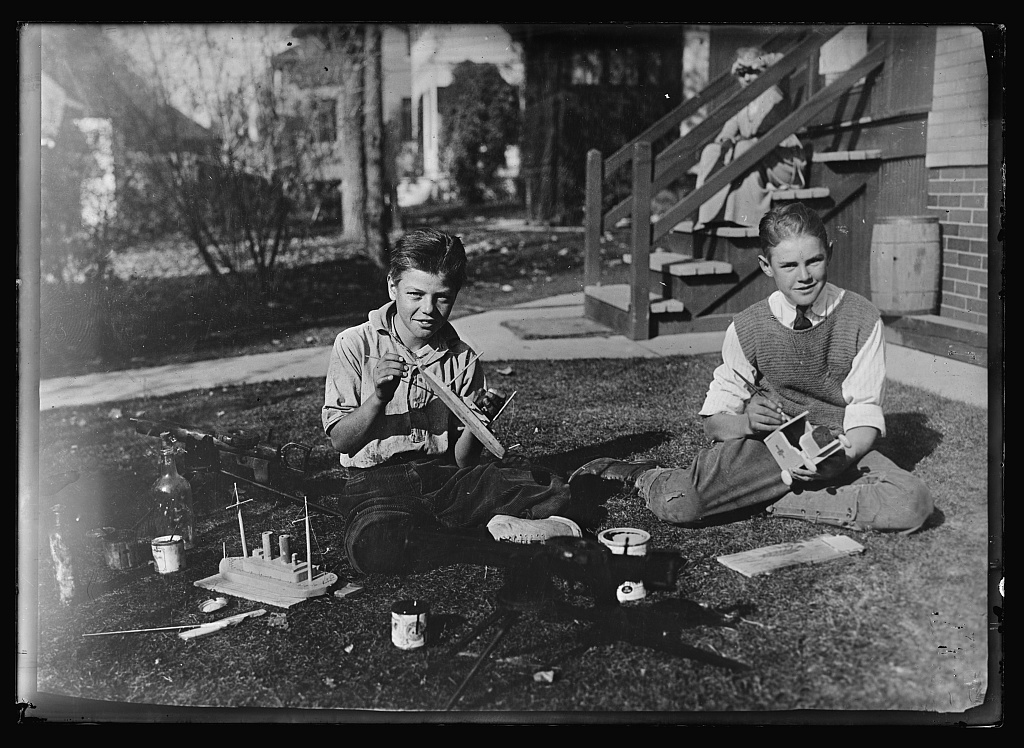

The Back-Yard Workshop, while School was closed for Influenza. Denver, 1919. Library of Congress

By October 4th, the number of cases and deaths had rapidly climbed. Denver Mayor W.F.R. Mills drafted an order closing all Denver schools, business colleges, Sunday schools, clubs, lodges, pool halls, movie theaters and any other building that encouraged public assembly. As a result, the population of Denver began to go outdoors, congregating in shopping districts and holding outdoor religious services. Realizing that gathering outdoors was just as harmful as being indoors, outdoor funerals and other outdoor assemblies were also prohibited. By October 15, the total number of cases stood at 1,440. Further restrictions were put in place including limited store and office hours and restrictions to the number of passengers on public streetcars.

According to the Municipal Facts published by the city of Denver, residents were not taking the epidemic as seriously as city officials and state health board had wished in the early stages. As the November issue stated:

People have a wholesome respect for typhoid, scarlet fever or smallpox signs and will, of their own violation, respect established quarantines… For some reason however, even the most enlightened citizens will not take the influenza epidemic seriously… They know that the disease is a deadly menace and snuffs out life almost before the victim realizes that he is ill. Yet when health officers try to impress upon the public the necessity of following essential rules and regulations, the average citizen simply refuses to heed these admonitions. Obviously, it is impossible to arrest the entire citizenship of the city and that is what health authorities would have to do if they attempted to enforce the rules to the letter.

By early November, the restrictions seemed to be working as the number of cases decreased. City officials met to discuss the end of the closures and began to allow some movie theaters and other large gathering places to open after midnight as long as they were not in a neighborhood where the epidemic were still raging. The immigrant neighborhoods of Globeville and Little Italy were still suffering, leading to immigrant backlash and scorn. Although restrictions were lifted, the city still warned citizens to limit gatherings.

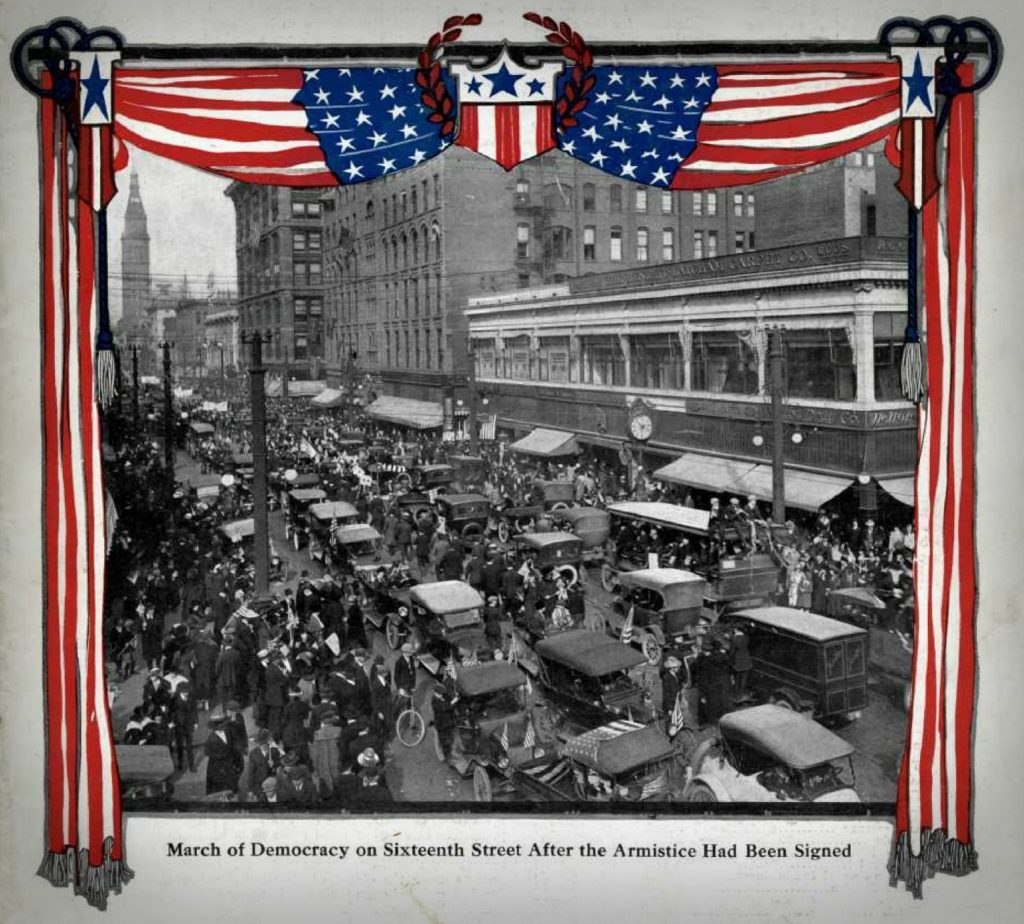

Armistice Day – Cover of the Municipal Facts Volume 1. No. 9 November 1918. Denver Public Library

Armistice Day – Cover of the Municipal Facts Volume 1. No. 9 November 1918. Denver Public Library

The restrictions in Boulder and Denver were lifted on November 11, 1918 for Armistice Day. Thousands of Colorado residents celebrated the end of war in the public auditoriums, hotels, theaters and movie theaters. In Denver, 8,000 attended the celebration in the city auditorium. An article in the November Municipal Facts, “The Day of World’s Liberty as Observed in Denver,” also describes the celebration:

The news reached Denver in the dead of night after the city had gone to sleep. Suddenly a great clamor broke forth; whistles blew, bells rang, and the harsh calls of newsboys brought citizens to bolt upright in bed with one word upon all lips—Peace! People poured from hotels and rooming houses downtown; automobiles, piled high with their shouting human freight, came honking from the residence districts into the business section, and a celebration had started that lasted with little intermission for forty-eight hours. Awakened by the tumult in the early morning hours, Mayor Mills proclaimed a public holiday and day of thanksgiving.

The celebrations resulted in an uptick in influenza cases as the desire for festivities superseded the need for caution. As the number of infected grew, doctors and nurses were soon overwhelmed with patients. At Denver’s St. Joseph’s Hospital, half of the nurses caught the flu and were taken to a separate ward. Buildings in towns across Colorado including schools, churches, rooming houses and city halls, were being repurposed into emergency hospitals. At the height of the epidemic, Denver reported as many as 200 deaths a week.

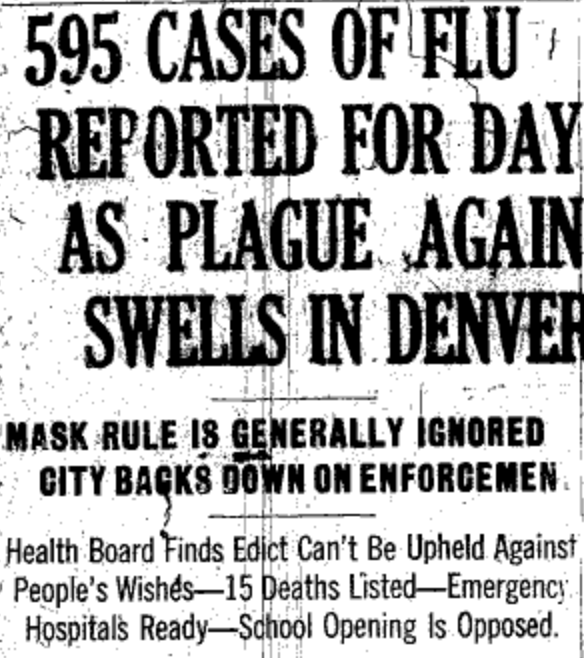

Denver Post November 26, 1918

Montrose Daily Press 1918

The city attempted to close public gathering spaces again, but the owners of the movie theaters and other public entertainment venues protested this plan. As a result, all Denverites were ordered to wear facemasks when leaving their house and entering any building. Due to confusion and a lack of masks, the general public, however, did not heed the order and many maskless residents conducted their business in downtown Denver. Threats of fines and arrest were impossible to maintain with a population of almost 250,000 people. By November 30, the mask order was annulled, and quarantine and isolation orders were made more robust.

Although new cases were reported through December, the infection rate was far less than in the previous months and life began to return to normal. Schools reopened in Denver on January 2, 1919.

The epidemic had come to an end, but the public continued to be cautious. Life wouldn’t be the same for the thousands of people in Colorado whose lives were touched by the influenza. Within the ten months of the epidemic, almost 8,000 Coloradoans, including 1,500 Denverites died, most of them in October, November, and December of 1918.

We do not know exactly how the Spanish Influenza touched the lives of the Browns personally, but Lawrence, Margaret and Helen, in different parts of the world, certainly would have read about the epidemic and seen its effects firsthand.

In August of 1918, when the first cases of the influenza were reported in New York City, Lawrence Brown, Margaret’s son, was on the fields of Ypres serving as an infantry captain with the American Expeditionary Forces. By October, Larry was lying in a hospital after being wounded by mustard gas at the Hindenburg Line in late September. After recuperating in field hospitals and in London, he was discharged in January of 1919, and quickly returned home to Colorado. Many were not as lucky. 53,000 US servicemen were killed in battle or died as a result of wounds during the war, but about 53,000 more servicemen were killed by the influenza that swept through Europe.

Influenza hospital ward in France, 12/28/1918. Courtesy of the National Archives.

Margaret Brown too would have seen and heard about the influenza through her efforts assisting in the war. She heeded an early call to support the war effort, donating her Newport cottage, Mon Etui to the Red Cross in 1914. She then sailed to France to establish a relief station. She traveled to Paris to assist in the ambulance service and was a member of CARD- The American Committee for Devastated France, which assisted with the rebuilding efforts of those areas devastated by the war. Paris was hit hard by the epidemic between September and December 1918 with a total of almost 8,000 deaths. Women were particularly vulnerable in Paris since most of the men were already fighting at the war fronts. Despite a mortality rate lower than 1918, Paris continued to be hit in the early months of 1919 with another 2,700 victims, including 1,000 in the month of February alone.

Helen Brown, Margaret’s daughter, now Helen Benziger, had been living in New York City since 1914. Although the city had a lower mortality rate than other large cities such as Philadelphia and Boston, New York still lost 30,000 people to influenza. Unlike Denver, schools and businesses never shut down. Instead, the city relied on disease reporting and a timetable of staggered hours for businesses and manufacturers to decrease the number of people gathering in spaces and on transit. Quarantine and isolation, including voluntary isolation and home quarantine, were also used to separate the sick from the healthy population.

When the dust from war and disease settled in 1920, it was a whole different world. “No more war, no more plague, only the dazed silence that follows the ceasing of the heavy guns; noiseless houses with the shades drawn, empty streets, the dead cold light of tomorrow Now there would be time for everything.” – Pale Horse, Pale Rider- Katherine Anne Porter

By: Jen Kindick, Museum Education Specialist

Sources:

Aimone, F. (2010) “The 1918 Influenza Epidemic in New York City: A Review of Public Health Response.” Public Health Rep. 125 (Suppl 3), 71-79. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2862336/

Erkoreka A. (2010) “The Spanish influenza pandemic in occidental Europe (1918–1920) and victim age.” Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 4(2), 81–89.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5779284/

Municiple Facts: Volume 1 Number 9, 1918 November.

https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll15/id/4296/rec/4

Porter, Katherine. 1936. Pale Horse, Pale Rider. Random House: New York.

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.184599/page/n271/mode/2up

The Denver Post. Nov. 26, 1918, pg.1, 3

http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2210flu.0004.122

For more information concerning the Influenza Epidemic in America:

https://www.influenzaarchive.org/