In Margaret Brown’s era, “Pink tea politics” suggested a frivolous engagement with political change, particularly among women of the upper classes of society. Progressive-era gatherings known as ‘pink teas’ were a socially acceptable way for women to organize and strategize in the pursuit of women’s rights, particularly the right to vote without the oversight or interference of men. From these gatherings, women were forming their own social organizations – Women’s Clubs and Literary Societies – which generated opportunities to engage in community work. These “pink tea” associations proved to be a breeding grounds for the suffrage movement.

When a chapter of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association was formed in Leadville, Colorado in 1893 by Mary C.C. Bradford, it is likely a young Margaret attended those meetings (unfortunately, those records no longer exist). Ten years later they were both members of the Denver Women’s Press Club. After moving to Denver in 1894, Margaret became a charter member of the Denver Women’s Club, led at the time by Sarah Platt Decker. By 1898 she was chairing the Art & Literature Committee, a group who prided itself on the building of River Front Park, a playground, and a summer school.

It was out here in the West, state by state, where women first gained enfranchisement. After a defeat in 1876, the Colorado Equal Suffrage Association campaigned for over a decade. To win the vote, Colorado women went door-to-door, organized letter-writing campaigns, and took part in speaking tours. As a result, Colorado was, technically speaking, the first state to grant women the right to vote as a referendum put to the voters in 1893 (Wyoming and Utah were territories at the time they granted suffrage).

Ellis Meredith, seen as the architect of Colorado’s passage of women’s suffrage, was nicknamed the Susan B. Anthony of Colorado. She joined the staff of the Rocky Mountain News in 1889 and was the long-time editor of a column titled “Woman’s World.” She also served as the first woman elected to the Denver Election Commission. After the successful Colorado campaign she became a resource on the topic of women’s suffrage, and continued to write and speak about what it meant to the women of Colorado to have the right to vote:

“Equal suffrage is not an end; it is a beginning. It is the commencement of responsibilities and opportunities so vast that time itself is hardly long enough to work out the problems set before us. For years our resolutions have begun with the familiar preamble, ‘We, as women.’ The enfranchised woman has passed to a higher plane. It is not we as women, nor we as men who will make this world better, but all of us, working together as human beings.”

Helen Ring Robinson was also an active member of the Denver community, and like Margaret Brown, participated in the activities of the Denver Women’s Club and the Denver Women’s Press Club. In 1912, Robinson became the first woman elected to the Colorado State Senate. As a senator, Robinson was concerned with labor reform and worked with Margaret Brown to resolve the Ludlow conflict in 1914. Mistaken newspaper reports in early 1914 pitted Margaret against Robinson in a race for senate, when in fact Robinson intended to keep her state seat, while Margaret aimed for one of Colorado’s two U.S. Senate seats.

Mrs. James J. Brown of Denver had been in the news all spring of 1914 for her offer to lead a regiment of fighting women in the impending war with Mexico, then for responding to the miner’s strike that had turned deadly in Ludlow, in southern Colorado. Margaret focused her speaking engagements on the situation of miners and their need for improved conditions and equal rights. She held salons and conducted a whistle-stop speaking tour around the state. “If I go into this fight I am going to win,” she said. “There will be no mincing matters- no pink tea policies. It will be a regular man’s kind of campaign, stump speaking, spread-eagle and all.”

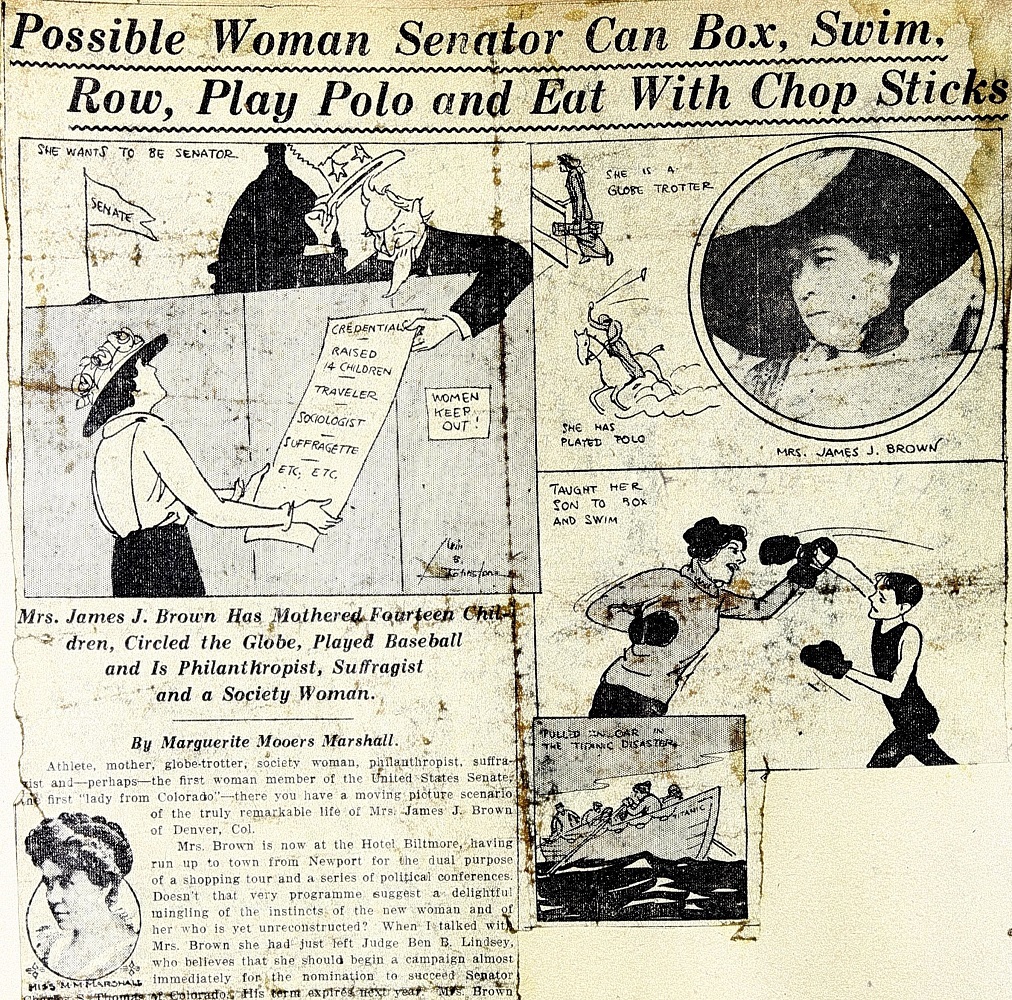

An original newspaper article covers an interview with Margaret Brown regarding her 1914 campaign for United States Senate. In the article, a series of cartoons show Margaret playing polo, boxing with her son, Larry, and presenting her credentials to the Senate over a fence with a sign, “Women Keep Out!”

From the Molly Brown House Museum archives

In this cartoon, she is presenting to the Senate a list of credentials that includes traveler, sociologist, and suffragette. It shows that she plays polo, taught her son to box and swim, and bent to the oar in the Titanic Disaster.

She had already been noticed by eastern suffragists in 1912 in the wake of the Titanic. The Woman’s Journal published a multi-page article linking the suffrage cause and Titanic. “When women cannot vote, the ship of state is like the steamship Titanic with only half enough life boats.” With only half of the population able to vote, the “Ship State” will sink under such monstrous perils as saloons, gambling, small pox, child labor, and poverty.

Author Alice Stone Blackwell, daughter of founders and first-generation suffragists Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, mentioned Mrs. Brown as a chivalrous voter who survived and says, “An effort has been made in some quarters to deduce from the wreck of the Titanic an argument against votes for women… It is absurd to fancy that chivalry is a tribute rendered by a voter to a non-voter as a sort of offset for the lack of the ballot.”

The Woman’s Journal also covered Brown’s senate bid in 1914. This bid to take U.S. Senator Thomas’s seat was in the wake of the incident near Ludlow, Colorado. Margaret was in the unique position to mediate because she was seen as a leader by Colorado women but she also knew John D. Rockefeller, the mine’s owner, socially. She tried at first not to take sides, but ultimately did support the miners against the Rockefellers and used her fame to put pressure on them to concede.

Eastern suffrage leaders inquired about Brown’s credentials. Maud Howe Elliott, leader of the Newport Suffrage League and Alice Stone Blackwell corresponded in reference to this Women’s Journal article which upheld Brown as “the right kind of suffragist.” In another article Brown says, “It is the most propitious time to send a woman to Congress, it will be a great service to women in the east.” And when asked about the more militant English suffragists she replied, “Well, they have tried for 20 years to get what they want with sugar, and now they have adopted men’s methods.”

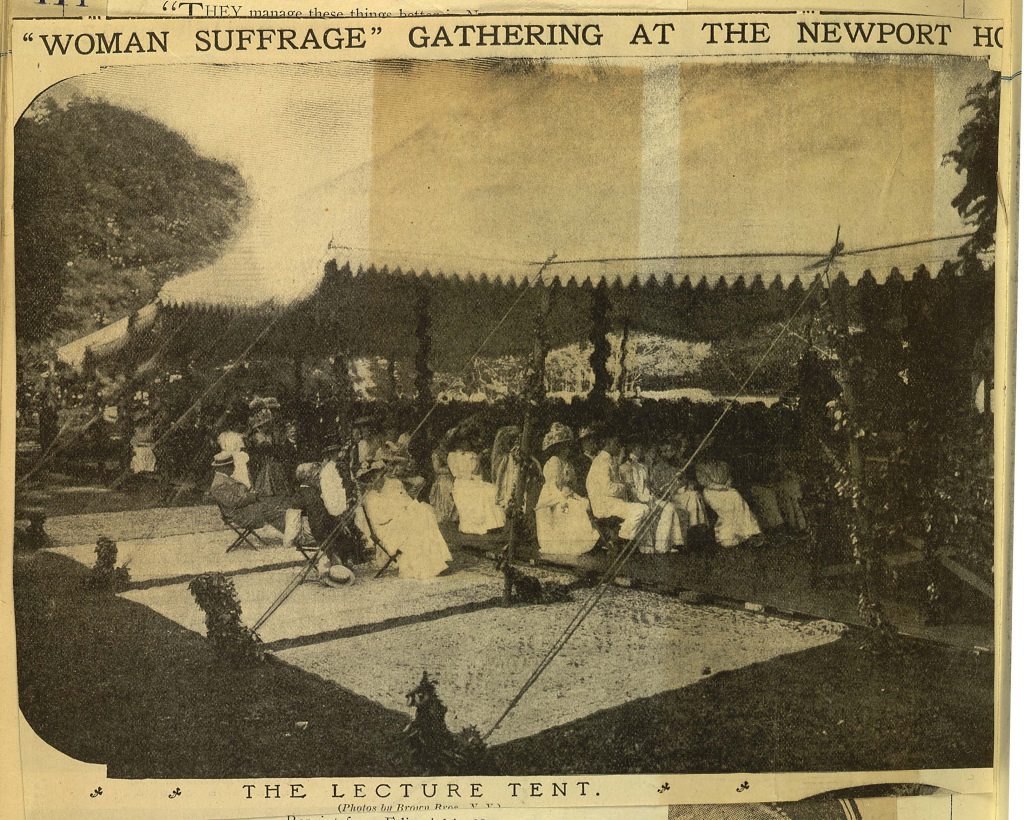

This was all unfurling as suffrage leaders, including Brown, gathered from across the U.S. for a “Conference of Great Women,” held at Marble House, the Newport, RI home of Alva Belmont, and included admission to her new Chinese tea pavilion. In the spirit of Seneca Falls, suffrage leaders and politicians from across the country attended, including Senator Robinson, who stayed with Margaret. During the conference Margaret also hosted at her cottage a speech by her dear old friend Judge Ben Lindsey. The Duchess of Marlborough, who was Belmont’s daughter, was also in attendance. Speakers included Florence Kelly, a political reformer and then head of the Consumer League who spoke on child labor; Rose Schneiderman of the National Women’s Trade Union; Katherine B. Davis who was then Commissioner of Corrections; and Harriet Stanton Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and then Pres. of the Women’s Political Union.

Marble House, the Newport, RI home of Alva Belmont, and included admission to her new Chinese tea pavilion. In the spirit of Seneca Falls, suffrage leaders and politicians from across the country attended, including Senator Robinson, who stayed with Margaret. During the conference Margaret also hosted at her cottage a speech by her dear old friend Judge Ben Lindsey. The Duchess of Marlborough, who was Belmont’s daughter, was also in attendance. Speakers included Florence Kelly, a political reformer and then head of the Consumer League who spoke on child labor; Rose Schneiderman of the National Women’s Trade Union; Katherine B. Davis who was then Commissioner of Corrections; and Harriet Stanton Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and then Pres. of the Women’s Political Union.

A month after the conference, the Congressional Union convened their own conference. Attendees included Alva Belmont, financier of the CU/NWP, as well as Alice Paul, Lucy Burns, and Doris Stevens, but also such notables as Inez Milholland, the famed beauty on the white horse in the 1913 parade on D.C., Dr. Cora Smith King of the National Council of Women Voters, Harriet Stanton Blatch, Florence Kelly again, women from dozens of regional suffrage associations, and Colorado’s own Senator Robinson and Margaret Brown.

In a letter from Alice Paul to Robinson, who had to return early to Colorado, Paul relates that the CU planned to conduct their 1914 election campaigns in suffrage states only and appeal to the women voters to withhold their support from the Democratic Party. Paul goes on to say that “this is the first time that suffragists ever entered a national political election,” and that “with 1/5th of the Senate, 1/7th of the House and 1/6th of the Electoral votes coming from suffrage states… such leverage could make possible speedy passage of Federal suffrage.” Here, for the first time, the plan of holding the Democratic Party—the Party in power—responsible for the slowness with which the Suffrage work was progressing was laid bare and submitted for Colorado’s approval.

Margaret Brown’s Senate bid is entangled in this nuanced final push for national woman’s suffrage. These competing approaches were splitting suffragists between the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) headed up by Dr. Anna Howard Shaw and then finally by Carrie Chapman Catt, and the Congressional Union (CU) headed by Paul, Burns and Stevens. Pauls’ CU followed the British approach to “punish the party in power” for not supporting suffrage.

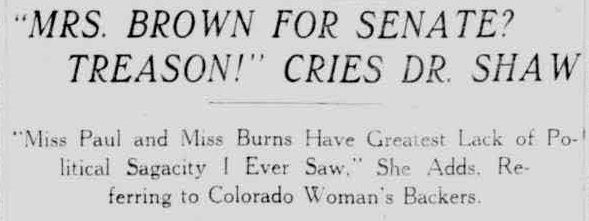

New York Tribune, July 24, 1914

As a Democrat, Senator Thomas was now under fire, but those back in Colorado like Bertha Fowler and Ellis Meredith knew that Thomas was actually pro-suffrage. As you can see in this headline, Dr. Anna Howard Shaw, then President of NAWSA, told reporters that Brown’s bid was nothing short of treason, and that “Miss Paul and Miss Burns have the greatest lack of political sagacity” in campaigning against Senator Thomas.” In response to Brown saying she wasn’t ready to sit down at 40 and mildew, Shaw retorted, “If she doesn’t want to mildew she better keep out of the US Senate.”

In a letter to CU’s Doris Stevens, Ellis Meredith related, “Now about Mrs. Brown… She is a good sort… only please refrain from campaigning against Senator Thomas, he was our friend before we had the suffrage, when friends were scarcer and more valuable.”

Letter from Ellis Meredith to Doris Stevens urging her that Margaret Brown should not run for Senate. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Stevens wrote to Lucy Burns in response to Dr. Shaw’s cry of treason by denying any official endorsement by the CU. Stevens relates her telephone call to Brown where Brown denies the statement but Stevens believes that the impression had been made, regardless. Whether or not that endorsement happened we may never know.

Ultimately, Margaret Brown decided not to run, based on the advice of Meredith, Senator Robinson, and perhaps that of Doris Stevens. And with the Bristow-Mondell and Shafroth-Palmer suffrage bills up for vote, she didn’t want to not upset the applecart back in Colorado. With war brewing in Europe, Brown’s attention were then drawn to France along with cohorts Anne Morgan and Anne Harriman Vanderbilt to set up nursing stations, drive ambulance, and rebuild France after the war.

By: Andrea Malcomb, Museum Director