One of the outlandish things that women in the Victorian era did was to adapt the cage crinoline as a way to achieve the sought after full skirt. Made of wood, steel, or horsehair, the crinoline was a stiff underskirt that made a woman’s skirt a force to be reckoned with.

While women reveled in the size and shape the crinoline could provide, alas, it was not all picnics and carriage rides. Because the large skirts extended so far beyond a woman’s body that they were hard to keep track of and indeed had a mind of their own. For starters, they were a serious fire hazard. Made often of cotton or gauze and swaying to and fro with grace and vigor, they easily caught on fire.

It is estimated that around 3,000 crinoline-fire deaths took place between 1850 and 1860. I am of the belief that this figure is quite inflated, but it does provide proof that such tragedy was not uncommon. Among the women who died were Longfellow’s wife and two of Oscar Wilde’s sisters. Keep in mind that not only were live fires much more common in the Victorian era when they were required for warmth, as with the corset, the crinoline was worn by all classes of women. Many a female member of the household staff was injured or killed when her dress was dusted with embers.

Machinery deaths and death after having one’s crinoline caught in a wagon wheel also appear in the various literature on the crinoline. An 1864 Irish newspaper, for instance, reports of a factory worker dying as a result of being mangled as her crinoline was caught:

“On Friday afternoon last she was engaged in the mangling room, and had occasion to go to a wall where, in a recess, soap is kept for the use of the workpeople, and about a foot from the wall a shaft between three and four inches in diameter, and two feet six inches from the floor, driven by steam power, revolves about fifty times per minute. Her dress was caught upon the shaft, and she was pulled to it, and revolved with the shaft two or three minutes before the machinery could be stopped. She was mortally injured in the spine. No limbs were broken. She died at home in two hours after the occurrence. A witness stated that her dress would not have been caught but for the crinoline pressing it out. The jury returned a verdict of “Accidental death,” adding a request that the shaft should be covered with a casing.”

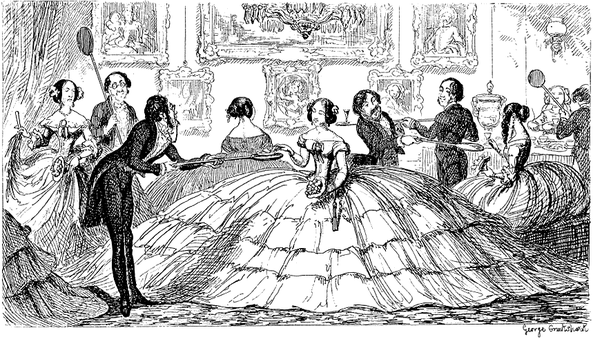

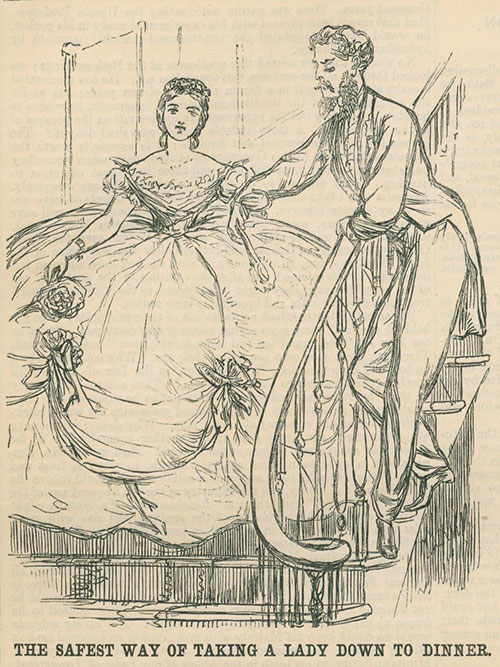

In the Branch article titled “15 August 1862: The Rise and Fall of the Cage Crinoline” scholar Rebecca Mitchell outlines the ways that the crinoline was criticized as well as adored. She also explains that men were also put at risk by the crinoline. Apparently, in the 1862s a man was crushed when trying to move between two boats, only to have his wife later revealed that the real reason he had tripped was to step around her large skirt. The comic here by Punch indicates that men’s safety and inconvenience resulting from the crinoline was of concern.

Mitchel also cites the following comment from a coroner following the 1862 death of an 18-year-old woman who’s skirt had succumbed to a flame: “if every fatal accident were reported, the public would know of them, and then he felt assured that crinoline. . . would soon be abandoned.”

Besides the many deaths by crinoline, as we can see from the illustrations, they were also heavily mocked by the (all male) press. Regardless, they would only go out of fashion as women traded in their preference for the size of the skirt to move from the feet to the rump and embraced the bustle. So, why did women wear them? Well, dear reader, to find out the rest of the story, and to learn more about the outrageous fashions of the Victorian era, join us Thursday, January 22 for Bloomers, Bicycles, and Bosoms.

By: Janice Formichella

Janice Formichella is a content writer, break-up coach, and history blogger currently residing in Denver, Colorado. A Molly Brown House Museum volunteer, she enjoys all things women’s history. You can follow her on Twitter at JaniceLikes and on Instagram at JaniceFormichella.