Sunday, July 26, 2020 marked the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This landmark civil rights law prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities “in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation, and all public and private places that are open to the general public.”[1] The ADA added to previous disability rights legislation including the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and 1975’s Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. The ADA “built on centuries of activism on the part of people with disabilities, and centuries of public debate over rights, citizenship, and engagement in civic life.”[2] The ADA brought public awareness to the environmental (physical) concerns confronting people with disabilities.

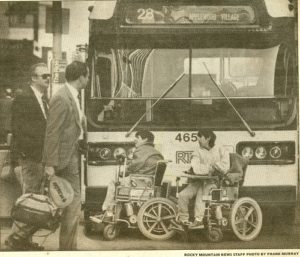

ADAPT members block a bus in Denver. Image courtesy of Denver Public Library, Wade and Molly Blank Papers (WH2283).

Denver drew national attention in July 1978 for protests against the Regional Transit District over the lack of wheelchair accessible buses. Protesters, known as the Gang of 19, physically blocked buses with their wheelchairs. When protests were arrested, police were unable to transport them to jail due to inaccessible police cars; instead, police officers erected barriers to detain the protesters because they had no other way to transport them, highlighting the lack of accessibility of the Denver Police Department. The Gang of 19 were part of a group that would become known as ADAPT who would go on to organize protests around the country, including the Capitol Crawl in 1990 which was organized to put pressure on Congress to pass the ADA.

The ADA applies to all places of public accommodation, including museums and other cultural facilities. Initially there was concern that this law would be onerous for historic sites, despite the fact that the law does not require that a historic property’s spaces, features, and significant materials be destroyed in the name of accessibility. The ADA, however, requires that barriers to access must be removed when it is readily achievable to do so. This term, “readily achievable,” means that it is easy to accomplish and can be done without too much difficulty or expense. Examples of readily achievable modifications include installing grab bars, ramping a few steps, lowering public telephones, and other similarly modest adjustments.[3] Historic sites should increase accessibility whenever possible, however, if the barrier removal threatens or destroys the historic significance of the building or facility, it is not considered readily achievable.[4] Now, thirty years from the ADA’s passing, we can see the concrete results of encouraging this type of introspection in the field of historic preservation. Many historic sites have incorporated not only ramps and lowered exhibit signage, but have also implemented sensory engagement activities that benefits all visitors. A large majority of historic sites have internalized the fact that providing access to people is a key tenant of their existence.

At the Molly Brown House Museum, our mission is focused on embracing the idea that culture is for all. The 1889 home, as built by architect William Lang, is not naturally accessible. The property has a hill, stairs, and numerous other obstacles, however, we have made a commitment to go beyond the letter of the law, and have been working diligently to make the museum and our programs accessible to all learners. In 2019, we completed a multi-year restoration and capital project. A key goal of this work was the installation of an accessible lift so visitors can access the museum’s first floor as well the basement-level Natural Resources Education Center and exhibit space. The installation of the lift required some alterations to the original structure, however we were able to confine it to a small corner of the enclosed back porch. An elevator that could reach all floors of the house would have required the removal of one of the historic bedrooms, which seemed too invasive to the historical integrity of the home, whereas changing a part of the back porch seemed well worth the alteration when weighed against the number of guests who can now access our space.

The piece of legislation we are celebrating is only one part of the story. Over the past thirty years since its passage, we have also experienced a shift in attitude. Historic buildings and sites are thinking outside of the box when it comes to modifying their historic structures to be more accessible. When limited budgets make drastically changing the structure of the building for accessibility improvements infeasible, we are seeing sites address accessibility through sensory items, videos, and touch items. For the areas of the Molly Brown House Museum that remain unreachable, even with the lift, we decided to create a video tour of these spaces that visitors can watch, along with a basket of touchable objects which highlight furniture, fabrics, and even architectural details that visitors see on the tour. We have also added specialized programs and resources for individuals with memory loss, those with sensory sensitivities, language barriers, and more.

The ADA is the start line, not the finish line, when it comes to accessibility. At the Molly Brown House Museum, we are continuing to look for new ways to make the museum even more accessible. Even with the current restrictions imposed by the safety procedures surrounding COVID-19, we have created a self-guided tour that can be downloaded on an individual’s phone, which includes an accompanying audio version. We also have downloadable versions of the tour available in multiple languages on our website. When we are able, we are looking to add touch tours for individuals who are blind or low-vision, sign language tours for individuals who are d/Deaf or hard of hearing, and tours/programs in multiple languages. We hope that the work we are doing will inspire other organizations, just like Margaret inspires us, to take action and do what they can to welcome people with disabilities into their buildings and sites.

By: Heather Pressman, Director of Learning & Engagement

Portions of this essay have been excerpted from The Art of Access, a forthcoming book on museum accessibility, and are used with permission of the authors.

[1]“What is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)?, ADA National Network, accessed February 8, 2019 https://adata.org/learn-about-ada

[2] Kim E. Nielsen, A Disability History of the United States, pp.180

[3] “Public Accommodations,” ADA National Network, accessed February 8, 2019, https://adata.org/publication/ADA-faq-booklet#Public%20Accommodations

[4] If the building or facility is designated as historic under state or local law or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places under the National Historic Preservation Act (16 U.S.C. 470, et seq.).