The use of make-up, hair products and perfumes is not a modern notion; these types of bodily decoration have been around since well before the ancient Egyptians. While each culture and time period have interpreted their beauty routines differently, the Victorians took it to an entirely new, and dangerous, level. From the products they placed on their faces, ways in which they washed their hair, and even the dyes used to color their dresses, it seems as if all forms of beauty in the Victorian age, should have come with a “buyer beware” warning.

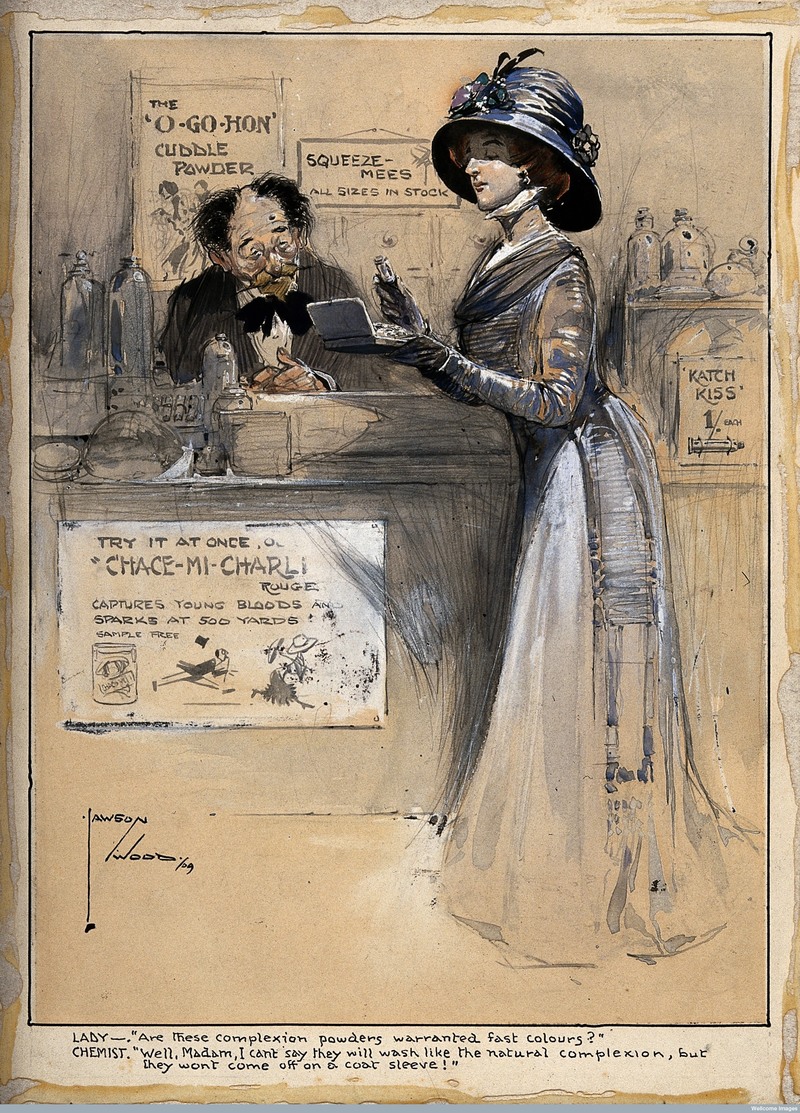

Arsenic has been a popular cosmetics ingredient, despite its known toxicity, for centuries.[1] However, presences of poisons in everyday life, particularly for a woman, were hard to ignore: “Glass and tin bottles hide snug in a case, waiting for a woman’s daily ritual. She reaches for a bottle of ammonia and washes it over her face, careful to replace the delicate glass stopper. Next, she dips her fingertips into the creams and powders of her toilet table, gravitating toward a bright white paint, filled with lead, which she delicately paints over her features. It’s important to avoid smiling; the paint will set, and any emotion will make it unattractively crack.”[2] One publication in particular, The Ugly Girl Papers , shed light on the practices that women were participating in every day, even offering suggestions on different, common poisons, to use themselves. Reminiscent of what was known in the 1990s as “He roine Chic”, there were two main makeup looks throughout the Victorian era: The “English Rose” and “Painted Lady”. The goal of the “painted” lady was to appear as pale as possible, a reminder to the rest of society that her privilege has afforded her to not have to work in the sun. Because of this societal ideal, it came as no shock that the highly sought after look quickly became modeled after those suffering from consumption, or tuberculosis. Alexis Karl, a perfumer who has researched Victorian cosmetics extensively, noted “the look of the consumptive was very desirable: the woman with the watery eyes and pale skin, which of course was from the cadaver in the throes of death.”[3]

roine Chic”, there were two main makeup looks throughout the Victorian era: The “English Rose” and “Painted Lady”. The goal of the “painted” lady was to appear as pale as possible, a reminder to the rest of society that her privilege has afforded her to not have to work in the sun. Because of this societal ideal, it came as no shock that the highly sought after look quickly became modeled after those suffering from consumption, or tuberculosis. Alexis Karl, a perfumer who has researched Victorian cosmetics extensively, noted “the look of the consumptive was very desirable: the woman with the watery eyes and pale skin, which of course was from the cadaver in the throes of death.”[3]

So just how was a look like that achieved? To attain the ‘watery eyes’, a woman would place belladonna drops directly into her eyes, this effect would last far longer than dropping citrus or perfume, as some women did. While belladonna would achieve the desired look, used over time it would render the user blind! To achieve the pale, translucent skin that would evoke purity, innocence and most importantly, class, women would go to extremes that would make some of us cringe today. One of the most popular notions of basic skin care at the time, was a mix between ammonia, mercury and opium; one was recommended to coat their face with opium overnight, followed by a “wash of ammonia” in the morning, and if sparse eyebrows or eyelashes plagued you, a quick wash with a mercury compound was recommended as a night treatment.[4] Ammonia was also commonly used to wash and style your hair. Looking for longer eyelashes, without the use of mercury? Eyelash extensions began to rise in popular thought in the 19th century; to start, cocaine would be washed not only across your eyelid, but on the interior rims of your eyelids as an anesthesia, then a technician would pluck a few hairs from your head, thread it through the eye of a sewing needle and get to work threading your “new” eyelashes onto your lash line.[5] In writings such as The Ugly Girl Papers, the author would be some what contradictory in both recommending that ammonia will help your hair to grow and be stronger, while also suggesting that the ammonia wash used on your face would help to rid you of any unwanted body hair.[6] Another popular face cream at the time was the French brand Tho-Radia, among many, used significant amounts of radium to help “brighten” a woman’s complexion.[7]

century; to start, cocaine would be washed not only across your eyelid, but on the interior rims of your eyelids as an anesthesia, then a technician would pluck a few hairs from your head, thread it through the eye of a sewing needle and get to work threading your “new” eyelashes onto your lash line.[5] In writings such as The Ugly Girl Papers, the author would be some what contradictory in both recommending that ammonia will help your hair to grow and be stronger, while also suggesting that the ammonia wash used on your face would help to rid you of any unwanted body hair.[6] Another popular face cream at the time was the French brand Tho-Radia, among many, used significant amounts of radium to help “brighten” a woman’s complexion.[7]

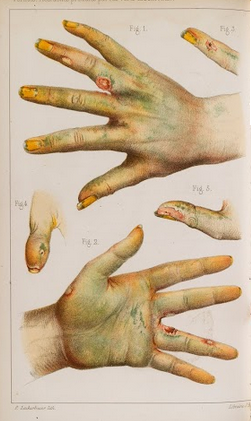

Arsenic complexion wafers became another increasingly popular avenue to achieve the pale color of virtue for a woman; offered in places such as the Sears & Roebuck catalogue and the local druggist, these types of wafers were advertised for delicate nibbling and were advertised as generally safe. It has even been recorded that in Bohemia (former portion of the Czech Republic and Slovakia), women would bathe regularly in arsenic riddled hot springs to lighten their entire body.[8] The use of arsenic, laced and formative, products in Victorian beauty products led t o a multitude of side effects from damage to the kidneys and entire nervous system, hair loss, arsenical keratosis growths throughout the body, vitiligo and ultimately death. Lead based cosmetics paints had been an extremely popular skin cover for decades before the Victorians grabbed a hold of it, and continued to rise in the 19th century; covering your face, arms, chest and any other piece of skin that was shown, the corrosive nature of lead would leave your skin damaged and in far worse shape after every use, requiring you to use more and more to cover up its effects.

o a multitude of side effects from damage to the kidneys and entire nervous system, hair loss, arsenical keratosis growths throughout the body, vitiligo and ultimately death. Lead based cosmetics paints had been an extremely popular skin cover for decades before the Victorians grabbed a hold of it, and continued to rise in the 19th century; covering your face, arms, chest and any other piece of skin that was shown, the corrosive nature of lead would leave your skin damaged and in far worse shape after every use, requiring you to use more and more to cover up its effects.

As if the cosmetics practices of the 19th century weren’t harrowing enough, the very clothes and sometimes very rooms, in which Victorians found themselves would lead to their demise. Although the dangers of arsenic were well known throughout the world, it was still an extremely popular ingredient in everyday products, including dyes. As we know from history, a garment is never simply, a garment. A garment is a physical representation of not only you, but your family’s status in society, and specific colors can represent varying different things; Victorians were green with envy. With a penchant for bringing the outdoors in, emerald green became an increasingly popular col or. The secret ingredients to get a pure emerald green in color? Mixing copper and the highly toxic arsenic trioxide, or “white arsenic” together.[9] This dye was used to make the greenery of fake plants pop, to color fashion gowns, color wallpaper, dye fabrics to cover furniture, etc. Dr. A. W. Hoffman wrote an article titled, “The Dance of Death

or. The secret ingredients to get a pure emerald green in color? Mixing copper and the highly toxic arsenic trioxide, or “white arsenic” together.[9] This dye was used to make the greenery of fake plants pop, to color fashion gowns, color wallpaper, dye fabrics to cover furniture, etc. Dr. A. W. Hoffman wrote an article titled, “The Dance of Death

”, wherein he proclaimed that ball gowns dyed green contained nearly half of their weight in arsenic, using the example that “a ball gown fashioned from 20 yards of this fabric would have 900 grains of arsenic” and could drop nearly 60 grains of arsenic in a single evening; 4-5 grains of arsenic would be lethal to an adult.[10] These dyes would also be used in wallpaper to decorate your home and to dye fabrics that covers your furniture.

Author Charlotte Perkins Gilman highlighted this household danger in her short story, The Yellow Wallpaper, “the smell…it creeps all over the house. I find it hovering in the dining room, skulking in the parlor, hiding in the hall and lying in wait for me on the stairs…Such a peculiar odor too! I have spent hours in trying to analyze it, to find what it smelled like.”[11] In 1839, German chemist Leopold Gmelin “noted that damp rooms with green wallpaper often possessed a mouse-like odour, which he  attributed to the production of dimethyl arsinic [sic] acid within the wallpaper.”[12] Many believed that they would be safe from the effects of these wallpapers as long as they refrained from licking it, or stayed away from the green colors, however, even if left untouched arsenic could flake off of the wallpaper or even form arsenic gas if the room became damp.[13] When put into the bounds of Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper, a woman is confined to a single room to help rid her of the female hysteria that was, clearly, taking over. The constant exposure to the arsenic laced wallpaper, coupled with isolation, led to the mental decline and assumed eventual death, of the main character.

attributed to the production of dimethyl arsinic [sic] acid within the wallpaper.”[12] Many believed that they would be safe from the effects of these wallpapers as long as they refrained from licking it, or stayed away from the green colors, however, even if left untouched arsenic could flake off of the wallpaper or even form arsenic gas if the room became damp.[13] When put into the bounds of Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper, a woman is confined to a single room to help rid her of the female hysteria that was, clearly, taking over. The constant exposure to the arsenic laced wallpaper, coupled with isolation, led to the mental decline and assumed eventual death, of the main character.

For those of us in the 21st century, we read about these types of beauty routines in absolute shock and horror; but we weren’t alone, the Victorians knew of these poisons and their deathly side effects, but simply chose to ignore them for the sake of beauty. The lesson learned? Beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, but arsenic, mercury, radium and lead would guarantee that you were… drop dead gorgeous.

Savannah R. Reeves

Education Programs Associate

[1]“Drop Dead Gorgeous: A Tl; Dr Tale of Arsenic in Victorian Life,” The Pragmatic Costumer, June 11, 2014, accessed February 3, 2017, https://thepragmaticcostumer.wordpress.com/2014/06/11/drop-dead-gorgeous-a-tldr-tale-of-arsenic-in-victorian-life/.

[2] Natalie Zarrelli, “The Poisonous Beauty Advice Columns of Victorian England,” AtlasObscura, December 17, 2015, accessed February 3, 2017, http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-poisonous-beauty-advice-columns-of-victorian-england.

[3] Zarrelli, “The Poisonous Beauty Advice Columns of Victorian England,”

[4] Zarrelli, “The Poisonous Beauty Advice Columns of Victorian England,”

[5] Cheryl Wischhover, “The Most Dangerous Beauty through the Ages,” TheCut, December 17, 2013, accessed February 3, 2017, http://nymag.com/thecut/2013/12/most-dangerous-beauty-through-the-ages.html.

[6] S.D. Powers, The Ugly-Girl Papers, Or, Hints for the Toilet (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1874), 125-27, accessed February 3, 2017, https://archive.org/details/uglygirlpapersor00powerich.

[7] Allison Meier, “Objects of Intrigue: Look Radiant in Radium,” AtlasObscura, June 25, 2014, accessed February 3, 2017, http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/objects-of-intrigue-look-radiant-in-radium.

[8] Lola Montez, The Arts of Beauty; Or, Secrets of a Lady’s Toilet (New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1858), 41, accessed February 3, 2017, https://archive.org/details/artsbeautyorsec00montgoog.

[9] Allison Matthews David, Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress Past and Present (n.p.: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), 74.

[10] David pg. 76

[11] Charlotte Perkins Gilman, The Yellow Wallpaper and Selected Writings (n.p.: Little, Brown Book Group, 2009),

[12]Jessica Charlotte Haslam Deadly Decor: A Short History of Arsenic Poisoning in the nineteenth century Jessica Charlotte Haslam, “Deadly Décor: A Short History of Arsenic Poisoning in the Nineteenth Century,” Res Medica: Journal of the Royal Medical Society 21, no. 1 (2013): 75-81, accessed February 3, 2017, http://journals.ed.ac.uk/resmedica/article/viewFile/182/799.

[13] Allison Meier, “Death by Wallpaper: The Alluring Arsenic Colors That Poisoned the Victorian Age,” Hyperallergic, October 31, 2015, accessed February 3, 2017, http://hyperallergic.com/329747/death-by-wallpaper-alluring-arsenic-colors-poisoned-the-victorian-age/.