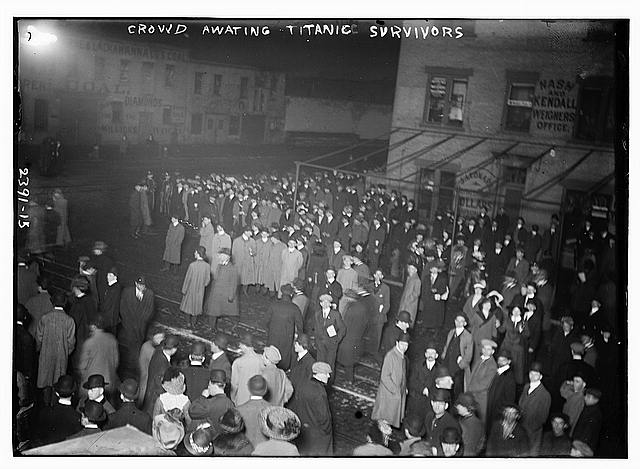

Once the Carpathia docked in New York City on April 18th, the reality of 1,500 lost crew and passengers devastated those waiting for news. The Halifax, Nova Scotia office of the White Star Line spent weeks recovering those lost at sea.

The SS Mackay-Bennett was the first ship ready to recover bodies. Commanded by Captain F. H. Lardner the crew quickly loaded over 100 coffins and embalming fluid. The Mackay-Bennett recovered 306 bodies, 116 were buried at sea and 190 taken to Halifax, Nova Scotia for burial.

The next ship to help in the recovery was the SS Mina. The Mina picked up 15 bodies; two were buried at sea and the rest returned to Halifax. Also sent was the SS Montmagn, which only recovered four bodies, one of which was buried at sea and the other three returned to Halifax. The last ship was the SS Algerine which only found one body.

Even before the search of the bodies was complete, the United States Senate investigation of the disaster began. The hearing ran from April 19 to May 25, 1912. Senator William Alden Smith of Michigan proposed the investigation and became the chief examiner. The Senate investigation questioned 82 witnesses including Chairman of the White Star Line J. Bruce Ismay, Second Officer Charles Lightoller, and Marconi operator Harold Bride. Mrs. J.J. Brown was not asked to testify at the hearings. She instead wrote a three-part account of her experience for the Newport Herald. Reprinted by newspapers across the country, her account strongly criticized White Star Line for how they handled the disaster.

A British Board of Trade investigation was also undertaken. This began on May 2 and ran until July 3rd, 1912. The presiding judge was Lord Mersey, Sir John Charles Bigham. 97 witnesses were questioned including Sir Cosmo and Lady Duff Gordon who had escaped in a lifeboat with only three other passengers and seven crewmen. Sir Cosmo offered each crewman five pounds to replace their belongings. To some, it looked as if this was a bribe for the crew for rowing away from those who were drowning. The inquiry concluded that they were not to blame, but the bad publicity damaged their reputations.

Both inquiries concluded that high speeds, coupled with a disregard for icy conditions led to the iceberg strike. The immense loss of life was a result of an inadequate number of lifeboats and poor emergency procedures.

As a result of the Titanic disaster, transatlantic regulations were changed to require enough lifeboats for every passenger, to perform mandatory lifeboat drills, and to standardize protocols for reporting hazardous conditions. Although many of the victims were never identified, Mrs. J.J. Brown, as chairperson of the survivor’s committee, would make it her life’s work to ensure they were all remembered.