DENVER’S HOP ALLEY AND CHINATOWN

Denver’s Chinatown was located in LoDo, near today’s Ballpark, and was derogatorily called “Hop Alley”. Today, nothing remains of Denver’s Chinatown other than a commemorative plaque near Blake and 20th. The boundaries of Denver’s old Chinatown were approximately 15th to 20th and from Market to Wazee. Denver’s Chinatown was the largest in the Rocky Mountain West. At its peak, Colorado was home to roughly 1,400 Chinese immigrants, most of whom lived in Denver.

In 1870, the Colorado Territorial Legislature passed a resolution encouraging Chinese to immigrate to the area as a means of meeting its chronic shortage of laborers. “Immigration of Chinese labor is eminently calculated to hasten the development and early prosperity of the Territory, by supplying the demands of cheap labor.”[1] Near the end of 1870, there were 42 Chinese living in Denver along Wazee St. (Some say that the name Wazee may mean “street of the Chinese” in Cantonese; however, William McGaa, one of Denver’s early settlers, named the street after one of his Indian wives. Wewatta Street is named after another one of his wives.)

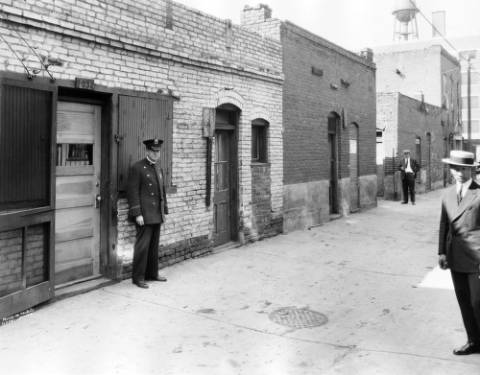

Originally called Chinaman’s Row, Denver’s Chinatown was established around 1870 between 15th and 17th Streets. It was located right next to the Red-Light District on Holladay Street (now known as Market). [2] Denver’s Chinatown earned the moniker “Hop Alley” because it was seen as a place where you could have an “exotic experience”. “Hop” referred to opium and “Alley” was in reference to where the entrances to buildings were. The era’s newspapers and yellow journalism tended to sensationalize the number of opium dens and other vices that were actually located in the area.[3] By 1880, there were 17 known opium dens in Denver, 12 in Hop Alley where one could “suck the bamboo” or “hit the pipe”.[4]

Originally called Chinaman’s Row, Denver’s Chinatown was established around 1870 between 15th and 17th Streets. It was located right next to the Red-Light District on Holladay Street (now known as Market). [2] Denver’s Chinatown earned the moniker “Hop Alley” because it was seen as a place where you could have an “exotic experience”. “Hop” referred to opium and “Alley” was in reference to where the entrances to buildings were. The era’s newspapers and yellow journalism tended to sensationalize the number of opium dens and other vices that were actually located in the area.[3] By 1880, there were 17 known opium dens in Denver, 12 in Hop Alley where one could “suck the bamboo” or “hit the pipe”.[4]

Many Americans believed the Chinese to be opium fiends. “The number of confirmed opium eaters in the United States is estimated at the terrible total of 100,000…The opium eater is, of all forms of humanity given over to destruction, the most to be pitied, and those who administer to the gratification of his vice are the most to be condemned.”[5] The irony is, while opium was legal in Denver in the nineteenth century, it was illegal in China.[6]

The Chinese “were thought to indulge in thought to indulge in immoral behavior, including opium smoking, high-stakes gambling, illicit sex, and presumably a few other vices unknown to the general public.”[7] They were described by the local press as a social menace who exerted a corrupting influence on innocent Denverites. Opium dens flourished in Denver’s Chinatown, in part because of the large number of white patrons. Dens on Arapahoe St catered to white women as well as the Chinese.[8] Most of the Chinese in Denver who did smoke were social smokers, including Denver’s first Chinese policeman, Louis Johnson, who admitted to smoking when he had a headache. The Chinese were most likely portrayed as addicts as a way to malign the minority since they were now considered “surplus labor” with the completion of the transcontinental railroad.[9] In 1914, the Harrison Narcotics Act made opium illegal.

Hop Alley was regarded as a notorious place, replete with brothels serviced by exotic women, gambling parlors frequented by glamorous people, and opium emporiums that catered to the drug cognoscenti. It was considered “an alien place, inhabited by people whose racial and cultural characteristics set them apart….a mysterious place that captured the imagination…”.[10] During Prohibition, there was also rampant bootlegging.[11]

Chinese bachelors (whether they had a wife in China or not) indulged in frequenting brothels, gambling, drinking, and smoking opium. While this sort of behavior was considered “entertainment” for whites, it was viewed as deviant in the Chinese. Chinese prostitutes were considered to be more perverse and morally degenerate than their white counterparts. One of the few recreational outlets available to the Chinese was gambling. Famous throughout the American West for their games of chance (such as cowpie poker), the Chinese were equally famous for their willingness to risk their hard-earned money. Denver’s Chinatown was a destination for Chinese from all over the state where they would try their luck in any one of many gambling establishments. The Chinese were not the only ones to visit Chinatown’s gambling houses—white patrons also came to take a risk on their favorite games of chance including roulette. Police began raiding gambling and opium dens periodically beginning in 1910 and closed them for good in 1927.[12]

Chinese bachelors (whether they had a wife in China or not) indulged in frequenting brothels, gambling, drinking, and smoking opium. While this sort of behavior was considered “entertainment” for whites, it was viewed as deviant in the Chinese. Chinese prostitutes were considered to be more perverse and morally degenerate than their white counterparts. One of the few recreational outlets available to the Chinese was gambling. Famous throughout the American West for their games of chance (such as cowpie poker), the Chinese were equally famous for their willingness to risk their hard-earned money. Denver’s Chinatown was a destination for Chinese from all over the state where they would try their luck in any one of many gambling establishments. The Chinese were not the only ones to visit Chinatown’s gambling houses—white patrons also came to take a risk on their favorite games of chance including roulette. Police began raiding gambling and opium dens periodically beginning in 1910 and closed them for good in 1927.[12]

Chinese immigrants arrived in Colorado as a source of cheap labor for the railroads and mines, “working cheaper than anyone else”. For those that chose to stay after this work ended, many opened hand laundry businesses. They were attacked as “dirty, filthy Chinese”, but the irony is they were the ones doing the laundry and also working as housecleaners.[13] The Chinese were portrayed as a boogeyman to scare white Denverites. An 1896 pocket guide recommended that visitors should apply for guides at the Central Police Station if they were planning on visiting the “Chinese quarters”.[14]

In reality, there were two Chinatowns, although they occupied the same space. The better known of the two was Hop Alley. The other Chinatown was an ethnic enclave much like other ethnic enclaves across the US. It was a place where Chinese immigrants could live among countrymen who could help them find a place to live, a job, and where they could socialize and practice their customs and traditions. In Chinatown, immigrants “could find goods and services denied them elsewhere”.[15] It brought together merchants and laborers. It served as a place for people who were heading off to construction projects and the mines to gather supplies as well as a place for rest and entertainment.

In reality, there were two Chinatowns, although they occupied the same space. The better known of the two was Hop Alley. The other Chinatown was an ethnic enclave much like other ethnic enclaves across the US. It was a place where Chinese immigrants could live among countrymen who could help them find a place to live, a job, and where they could socialize and practice their customs and traditions. In Chinatown, immigrants “could find goods and services denied them elsewhere”.[15] It brought together merchants and laborers. It served as a place for people who were heading off to construction projects and the mines to gather supplies as well as a place for rest and entertainment.

Denver’s Chinatown, like most others, was a bachelor society consisting of mostly young men. Racism prevented Chinese immigrants from entering into most occupations forcing approximately 80% of them to work in laundries.[16] However, some of the residents worked in other occupations: there were three servants, three barbers, a butcher, a restaurant worker, six cooks, two porters, two doctors, nine shopkeepers, four grocers, three clerks, and 17 cigar makers.[17] Businesses, for the most part, provided “ethnic-related goods and services” which allowed Chinatown to be a somewhat self-sufficient community.

With the completion of the transcontinental railroad, Denver grew rapidly. Many of the new residents came to Denver for its dry, sunny climate to aid their tuberculosis. Denver became knowns as the “sanatorium of the world” and had a reputation to protect. When Denverites started contracting the disease, the Denver Medical Association issued “dire warnings that precautions were needed to prevent the outbreak of epidemics citing downtown Denver, where Chinatown was located, as a place of particular concern.”[18] The Denver City Council was galvanized into action after the Typhoid epidemic of 1879-80. They created a Board of Health and authorized passing health ordinances, and began planning for the city’s first sewer system. In the meantime, Denver’s Chinatown was “singled out as a warren of disease that needed to be eradicated.”[19]

Chinatown was one of the poorest and most ethnically diverse areas of the city, located near other ethnic enclaves such as the Italians who lived in “The Bottoms”.[20] It was reportedly one of the dirtiest parts of one of the dirtiest cities in the country. “It’s streets were littered with the carcasses of dead rats and cats, open sewers were common, refuse was simply dumped into the Platte River downtown, and, in keeping with the city’s image as a ‘cowtown,’ livestock including pigs and cows were allowed to run loose on city streets.”[21]

Denverites were familiar with the idea that all Chinatowns were full of filth, “centers of contagion”[22], and warrens that needed to be eradicated. Despite the fact that there had not been an outbreak of disease in Chinatown, Rocky Mountain News led a crusade to eliminate the area and relocate its “500 loathsome Chinese”. They described it as a “noisome hive that constituted a health and fire danger to the downtown business district”. [23] The Board of Health supported the destroying and replacing of the businesses and residents in Chinatown because it was perceived as a breeding ground for potential diseases of all kinds.

Anti-Chinese Sentiment and Riot of 1880

The first Chinese immigrant reportedly arrived in late June 1869. Anti-Chinese acts began as early as 1871 when vandals set fire to a Chinese house, and only intensified after that.[24] Despite a reputation for being great workers, reliable, and industrious, Chinese immigrants were scapegoats for prevailing economic woes.

Building tensions between local residents and Chinese immigrants erupted on Halloween in 1880, resulting in the city’s first race riot. Within hours the mob destroyed businesses, residences, and temples. One man, Sing Lee, was killed during the melee. Nationally, the anti-Chinese movement had been building since the 1870s when Denis Kearny, an Irish immigrant himself, led a campaign to ban Chinese immigration fearing that Chinese labor would threaten the white working class. At the time of the riot there were 238 Chinese residents in Denver. In the days leading up to the riot, local newspapers fanned the flames of anti-Chinese rhetoric. One newspaper called the Chinese the “Pest of the Pacific” and pointed out that if they “invaded” Colorado in greater numbers, white men would starve and white women would be forced into prostitution. Other editorials attacked the opium dens located along Hop Alley. Three days before the riot, it was reported that there was open talk in Denver of running the Chinese out. The night before the riot, supporters of the Democratic Party marched in the streets carrying anti-Chinese banners.[25]

The riot broke out at John Asmussen’s Saloon, located in the 1600 block of Wazee. According to Asmussen, a white man and two Chinese were playing pool when three or four drunken white men entered the saloon and began quarreling with them. Asmussen later said:

“One of the Chinamen asked them to quit; the men them commenced abusing the Chinamen, and I remonstrated them and said they were as Chinamen and they came up to the bar and got some beer. While they were drinking, I advised the Chinamen to go out the back of the house to prevent a row and they went out at the back door. After a few minutes one of the white men went out at the back door and struck one of the Chinamen without any provocation. Another one of the crowd called to one of the gang inside to “come on Charley, he has got him.” and he picked up a piece of board and struck at the Chinese…. This was the beginning of the riot.”[26]

By 2pm there was a crowd of about 3,000. Denver’s police force was understaffed and without a chief at the time, and was unable to control the masses. The mayor tried to get the crowd to disperse and when they wouldn’t he ordered the fire department to turn the firehoses on them. The crowd grew angrier and began throwing bricks and rocks at the firemen and then turned their rage on Chinatown. By early evening, rioters had burned every laundry in Chinatown.[27]

In 1880, Denver’s police force only numbered 25-35 men. Only 8 men were on duty at the outbreak of the riot. The mayor appointed a fireman acting police chief. He quickly appointed 125 special policemen to help reestablish order. Authorities rounded up and locked the Chinese immigrants in the jail for their own protection. They were released a few days later to find their homes, businesses, and temples destroyed. Estimates of the damage exceeded $53,000. No claims were ever paid. Rioters who were jailed were released on lack of evidence and Sing Lee’s murderers were acquitted in February 1881. Despite the violence and destruction of property, many Chinese remained in Denver rebuilding their homes and businesses. By 1890 more than 980 Chinese lived in Denver.[28]

In 1870, there four Chinese living in Denver, out of a total population of 4,759. In 1880, the Chinese population was 238 out of 35,629. In 1885, five years after the riot, the Chinese population was 461 out of 61,491. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the introduction of steam laundries marked the beginning of the decline of the Chinese community in Denver and elsewhere.[29] In 1890, the population of Chinatown was at its apex of 980 of 106,713.[30] After 1890, the Chinese population in Denver began to dwindle. In 1900 the population was 599. In 1910, 373. In 1920, 291. In 1930, 233. In 1940, 110 people consisting of three families and a group of elderly Chinese men. Chinatown had become a “miserable neighborhood” and was replaced by small factories and warehouses in the post-World War II period.[31]

[1] “Denver’s Anti-Chinese Riot, 1880”, Roy Wortman

[2] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 67-68

[3] “Remembering When Denver had a Chinatown”, Denver Post, May 6, 2011.

[4] LoDo Walking Tour Plaque

[5] Rocky Mountain News Weekly, July 14, 1875

[6] The Qing dynasty condemned the consumption and sale of the drug and fought the Opium War against Britain (1839-42) in an effort to suppress drug trafficking, however, they lost the conflict (the British were the principal smugglers of the drug into China.) Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 93

[7] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 65

[8] “Denver’s Anti-Chinese Riot, 1880”, Roy Wortman

[9] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 94-95

[10] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 65

[11] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 65

[12] Denver Post, July 22, 1963

[13] “Remembering When Denver had a Chinatown”, Denver Post, May 6, 2011.

[14] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 65

[15] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 67

[16] http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.asam.010.xml

[17] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 73

[18] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 71

[19] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 72

[20] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 68

[21] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 71

[22] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 72

[23] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 72

[24] “Denver’s Anti-Chinese Riot, 1880”, Roy Wortman

[25] http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.asam.011.xml

[26] “Denver’s Anti-Chinese Riot, 1880”, Roy Wortman

[27] http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.asam.011.xml

[28] “Denver’s Anti-Chinese Riot, 1880”, Roy Wortman

[29] http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.asam.010.xml

[30] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 73

[31] Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State, 94-95