ART LEISENRING’S QUEER CAPITOL HILL

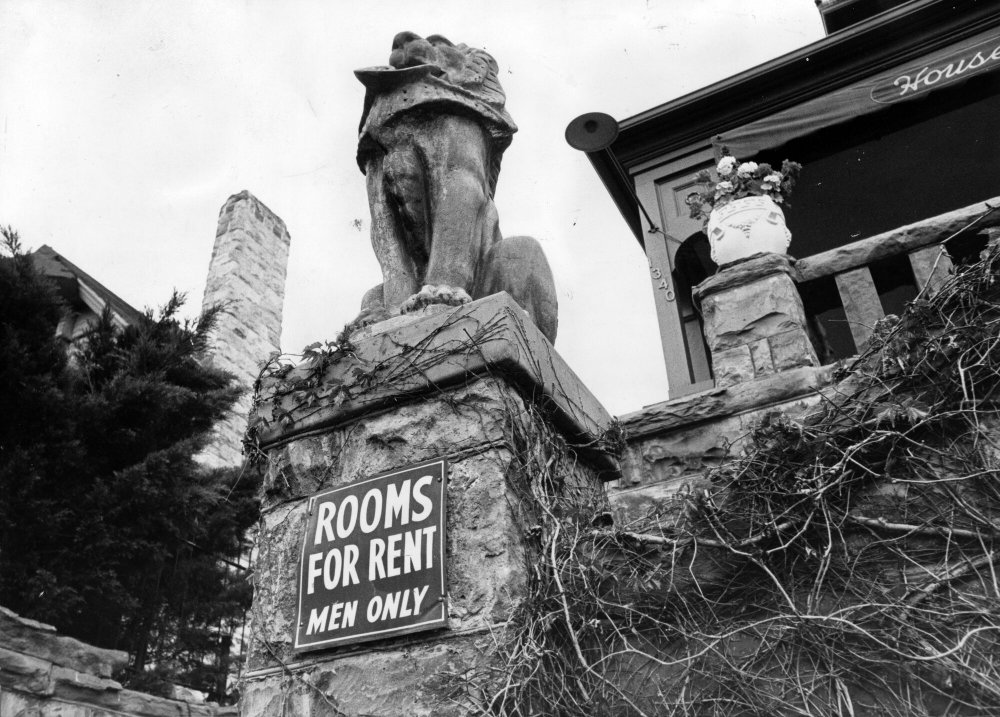

When Art Leisenring purchased the house at 1340 N. Pennsylvania St. in 1958, Denver’s Capitol Hill neighborhood was at the center of the city’s queer community. Art primarily ran the home as a boarding house, with renters living in the basement, second, and third floors, and Art living on the first. Zoning laws in Denver meant that most of the city’s multi-unit, or multi-family, homes were confined to Capitol Hill, and Art’s House of Lions was no exception. Like many queer neighborhoods throughout America, Capitol Hill saw significant “overlap between areas with a high gay and lesbian population and high numbers of both renters and multi-unit housing.”

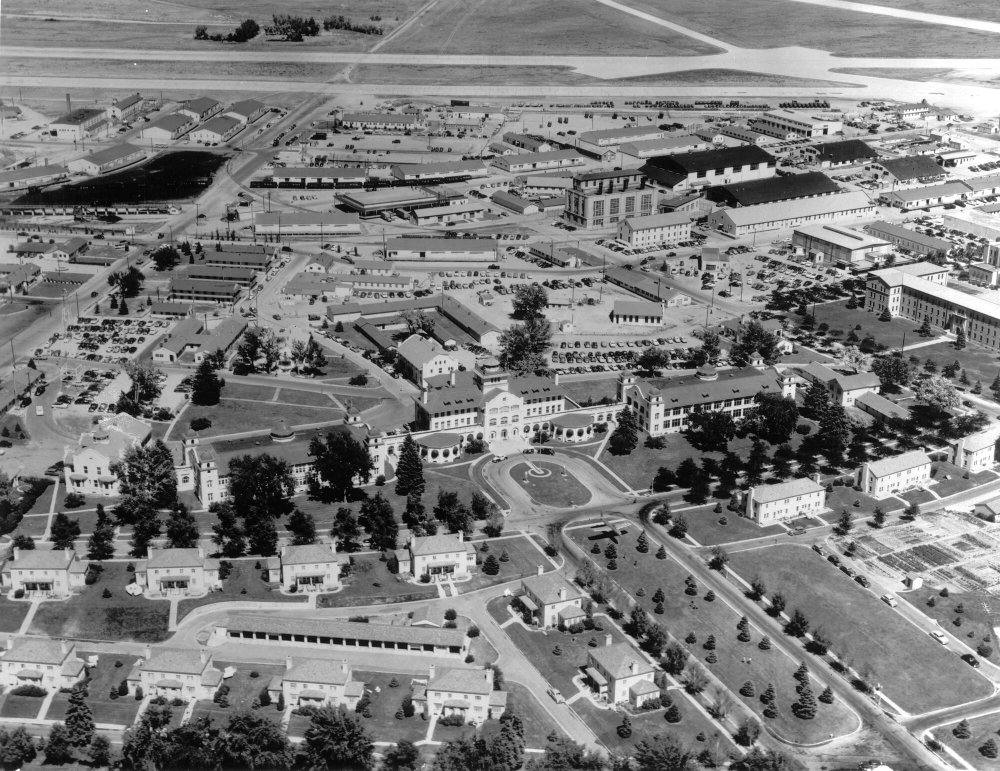

Capitol Hill and Denver saw a rise in population as well following the end of World War II. While some GIs were merely returning home, many others decided to move to the city after being stationed throughout Colorado at places like Camp Hale and the Lowry Air Force Base. Many elements of the war additionally fostered the creation of a queer community and subculture throughout the United States. According to historian Tom Noel in his article “Gay Bars and the Emergence of the Denver Homosexual Community,” “The mobilization of millions of men into a womanless world and the general loosening of morals during wartime fostered homosexuality in military barracks and bars.” Furthermore, Michael Bronski writes in Gay Male and Lesbian Pulp Fiction and Mass Culture that World War II was “the first time in American History that large-scale, highly organized, single-sex social arrangements were considered vital to national security.” It is from this period, then, that aspects of queer subculture began to emerge. Denver, for example, only had one explicitly gay bar before the war—The Pit, which opened in 1939. However, more gay bars were created both during the war and after. Some, like Mary’s Tavern, were transformed into a gay bar when Airmen from the Lowry Air Force base began visiting and acting “blatantly gay in behavior.”

1954, aerial view of Lowry Air Force Base. Photo courtesy of Denver Public Library

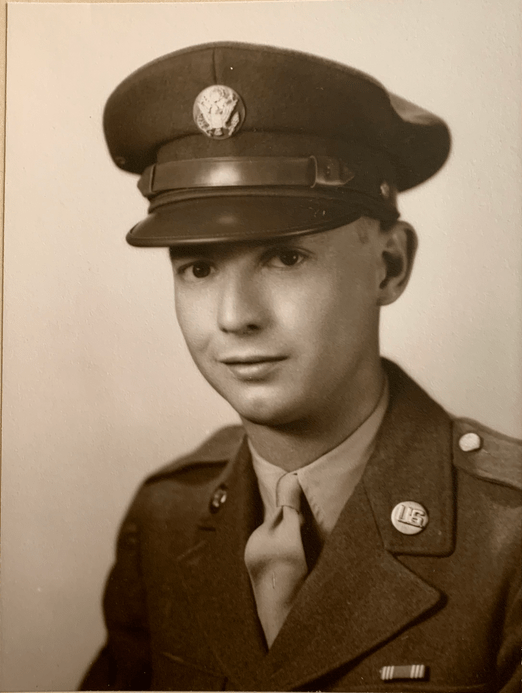

In 1942, Art Leisenring joined the United States Army Air Force and was stationed at Marana Air Force base in Arizona. A few months after the war ended, Art was honorably discharged in December, 1945 and returned home to Denver. It is unknown if Art participated in any kind of queer community or subculture while he was in Arizona. However, by the time he returned to Denver, development of the city’s queer community was well under way. The same Airmen who visited Mary’s Tavern had begun frequenting other bars along Broadway, and Capitol Hill’s queer community was becoming increasingly visible. In May 1949, the Denver Post published an article stating that “homosexuality in the city has reached an ‘all-time high.'”

Art Leisenring, MBHM Collections

Capitol Hill in particular had become a known gay neighborhood in Denver by the 1950s. As a gay man himself, Art likely would have known about Capitol Hill’s reputation when he decided to purchase the House of Lions in 1958 and operate it—at least for a few years—as a Men’s Only Boarding House. His niece, Arlene Myles moved in with her roommate Susan Clark in 1964, and in the late 1960s the home was a halfway house for wayward girls.

Lion Statue at 1340 Pennsylvania Street. Photo courtesy of Denver Public Library

Art met his partner in 1964 when he hosted a party to celebrate the premiere of The Unsinkable Molly Brown film. While being a queer person in the 1960s still had its risks, it was comparatively safer than previous decades had been. The years following World War II brought queer existence further into the public consciousness. Even though 1960s Denver was still considered a largely closeted space, more and more gay bars were popping up throughout the city and queer people were finding covert ways to communicate and meet. On June 28, 1969 in Greenwich Village, New York, police raided the Stonewall Inn. Police raids on gay bars were common throughout the 1960s and the 1969 raid on the Stonewall Inn was another in a long line of regular harassment against the queer community. However, unlike previous raids and harassments, the community at Stonewall refused to back down. When a lesbian was arrested, hit with a club, and thrown in the back of the patrol wagon, the crowd—by then about 600 people—erupted and started to riot. The effects from Stonewall rippled throughout the nation, including in Denver and many Pride celebrations today still commemorate the event.

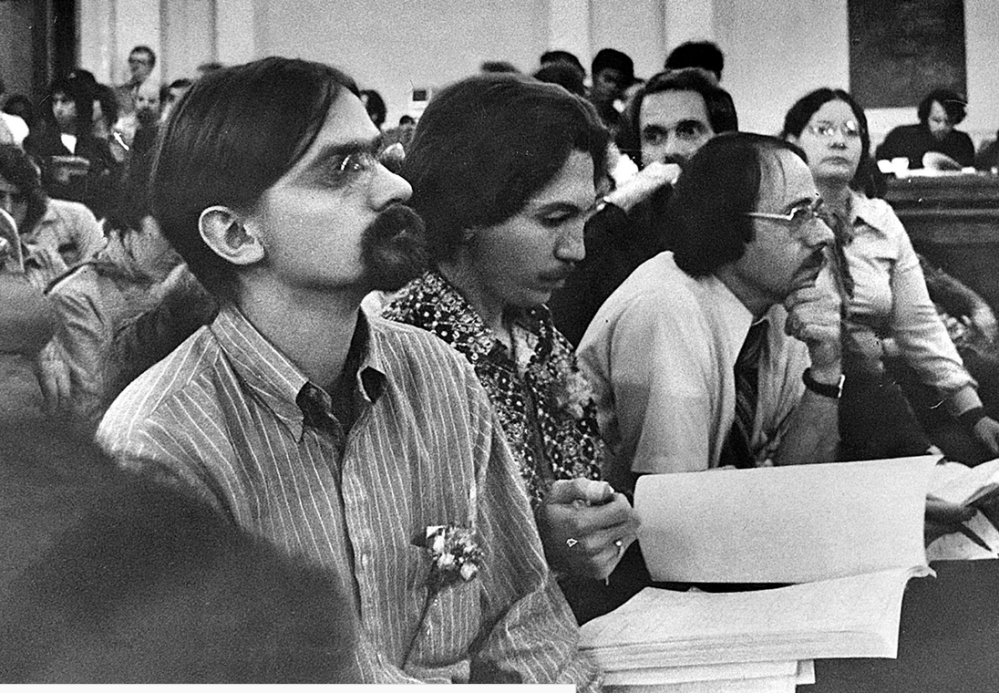

In 1972, the Gay Coalition of Denver (GCD) was formed and in 1973 they led a revolt of Denver’s City Council—now referred to as Colorado’s Stonewall. Even though Denver had repealed its sodomy laws in 1972, there were still laws against same-sex affection and behaviors that were considered “lewd and lascivious.” According to David Duffield in his exhibit Lavender Hill: Then and Now, “Police often entrapped gay men by initiating contact and then arresting the target if the conversation became sexual in nature. Between January and March of 1973, 380 gay men were arrested in these operations. Records proved that 100% of arrests for lewdness were gay men and 99% were initiated by the police, not the civilian.” Countless people spoke in front of the city council, and the proceedings went well into the morning. But they were successful. Within the next month, those discriminatory laws were repealed and LGBTQ+ harassment decreased throughout the city.

Terry Mangan, Cordell Boyce, and Gerald Gerash, Gay Revolt at Denver City Council. Photo courtesy of Gerash and reprinted in LGBTQ Denver by Phil Nash

While conditions were improving for the queer community throughout the remainder of the 20th century, there were still significant setbacks. The HIV/AIDS crisis emerged in the 1980s and, as Phil Nash writes in LBGTQ Denver, “the ugly spectacle of societal homophobia could no longer be ignored.” Tens of thousands of people passed away from HIV/AIDS during the 1980s and 1990s, and treatment for the disease wasn’t available until 1996. In 1992, Colorado voters passed Amendment 2, which would have eliminated existing protections against sexual orientation in Denver, Boulder, and Aspen as well as prohibit future protections at either the state or local level. Fortunately, this was ruled unconstitutional by both the Colorado Supreme Court and the United States Supreme Court and the amendment never went into effect. The response to these events represents the growing awareness of a queer community and culture throughout the United States, though evidently this was not always for the better. However, the overturning of Amendment 2 in Denver “cemented the resolve among LGBTQ people to become visible and mighty forces in… every part of the social structure that had…contributed to their oppression and stigmatization.”

Buttons advocating for the overturn of Amendment 2. Image courtesy of Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum

As far as we know, Art Leisenring was not publicly out as a gay man in Denver. It is only from recent interviews with his family and loved ones that we can now say he was. However, when they were together, Art and his partner did enjoy profound support from their families and close friends, and it’s easy to see that Art is still well-loved and dearly missed. As Art’s partner said, his mother was wonderful; “she accepted [him] and accepted Art being who we were – lovers.” It may have just been coincidence that they met and fell in love in one of Denver’s gayest neighborhoods, but the work that Art did was very intentional. His work throughout the city—helping establish Historic Denver and save the Molly Brown House, and his work with the MaxFund Animal Adoption Center—have cemented his legacy and his place in Denver’s history.

Researched and Written by Abby Wedlick, Collections Staff