A MODEL CITIZENSHIP: DOING OUR PART IN 1918 AND IN 2020

Armistice Day, 1918. Courtesy of Denver Public Library

102 years ago, a powerful strain of the flu swept the globe, infecting one third of the world’s population. Despite being called the Spanish Flu, is believed to have begun at US Army Camp Funston in Kansas earlier in 1918, and spread across the world via troop movement. The 1918 pandemic left more than 50 million people dead, including around 670,000 in the United States.

Margaret Brown would have read the Thanksgiving week headlines seen across the US in 1918 which said “Cities in lockdown! Thanksgiving celebrations are restricted! Vaccine trials underway!” Dozens of cities, including Denver, implemented face mask orders and curfews, and closed schools, libraries, theaters, and churches just like today. Denver also opened three emergency hospitals and issued an urgent call for nurses.

World War I, which concluded just as the flu was at its worst in November 1918, killed around 17 million people – a 1/3 of the number of fatalities caused by the flu. More American soldiers died from the flu than were killed in battle, and many of the deaths attributed to World War I were caused by a combination of the war and the flu. Margaret’s son Larry served in Northern France in the later days of the war and was exposed to mustard gas. He spent months recovering and managed to avoid a worse fate with the flu.

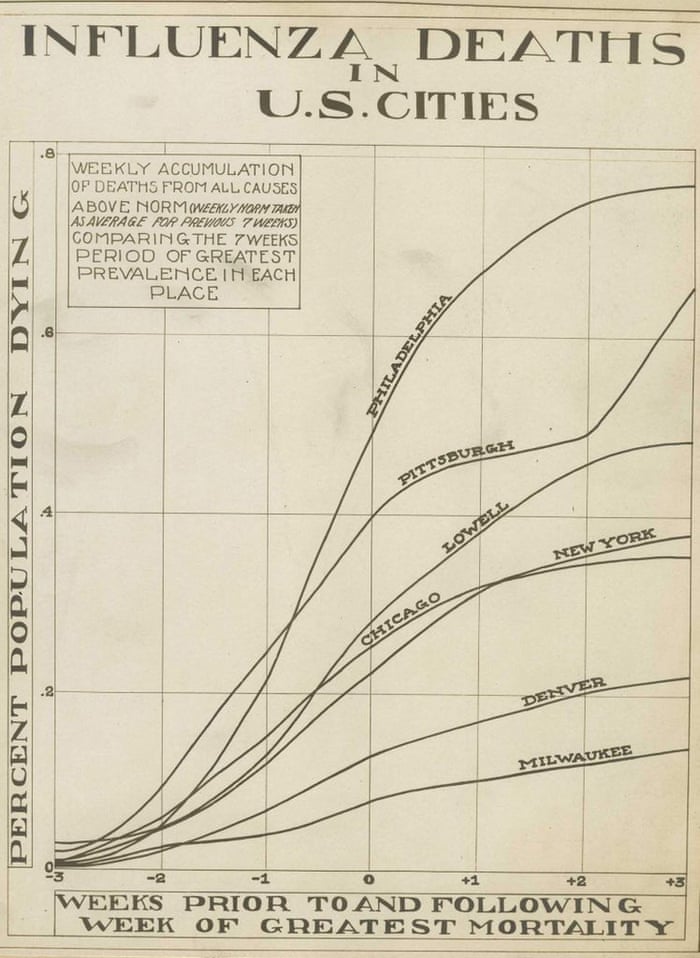

1918 Flu graph.

Victory day or Armistice Day on November 11th became what we would now call a super spreader event as cities around the world saw people flooding the streets to celebrate the end of the war. “It is not the lifting of the closure ban that is the cause of spreading of the epidemic but the putting aside of all precautions and restrictions by the people of Denver when they celebrated on Victory Day,” City Manager of Health and Charity William H. Sharpley told the Denver Post in a story November 21, 1918.

In Denver, the first recorded flu-related death was on September 27, when a student from University of Denver named Blanche Kennedy died after visiting Chicago, one of the hardest hit cities. Denver moved quickly, shutting down indoor gatherings on October 6, but by October 15 there were already 1,440 cases in a city of a quarter million and with only 300 doctors. Even in those early days of public health, with limited scientific remedies, social distancing and masks were understood to help stem the tide of pandemic, yet 195,000 Americans died of influenza in October of 1918 alone.

Some folks were upset at being asked to stay indoors and businesses were irritated at losing so much money due to what seemed like an isolated occurrence. Many tried to blame immigrants, the poor, and here in Colorado, Native American tribes for spreading the disease. Denver business owners marched on City Hall, protesting that they were losing tens of thousands of dollars a week. They argued it was better to simply quarantine those who showed symptoms and stigmatize the sick by placing signs on the houses where there had been a case of the flu, and let everyone else go about their business as usual.

The aftermath of this health disaster, however, led to unexpected social changes, opening up new opportunities for women and in the process transformed life in the United States. Suffragists had been fighting for women’s right to vote for 70 years, and victory seemed almost in reach. Even with the United States fully mobilized for World War I, President Woodrow Wilson had come out in support of a constitutional amendment enfranchising women, and the House of Representatives had finally passed it.

“These are sad times for the whole world, grown unexpectedly sadder by the sudden and sweeping epidemic of influenza,” wrote Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, in a letter to supporters in 1918. “This new affliction is bringing sorrow into many suffrage homes and is presenting a serious new obstacle in our Referendum campaigns and in the Congressional and Senatorial campaigns,” she continued. “We must therefore be prepared for failure.”

Faced by bans on public gatherings, suffragists switched to the personal touch, reaching out directly to neighbors and friends. They emphasized their patriotism and quoted the president saying that votes for women was a proper reward for their wartime sacrifice. National headquarters provided more than a million pamphlets for distribution door to door and 300 weekly bulletins for placement in local newspapers. Women signed petitions urging male voters to pass the state suffrage referendums up for vote.

Between the war effort and the flu response, suffragists endeavored to show a kind of “model citizenship.” “While the public spectacles were extremely valuable in keeping the issue in the news and in people’s minds, like the work of the Silent Sentinels, the more moderate suffrage work gained approval from public officials.” And this approval furthered the argument that women’s suffrage was socially acceptable.

Many suffragists saw these obstacles as opportunities to show their patriotism and contribution to the national effort. Local women’s groups volunteered with the Red Cross and while rolling bandages came first, later their work was to help discharged soldiers recover from the flu. It was also a moment of possibility for a more diverse group of women as during the pandemic, black nurses were admitted to the Army Nurse Corps and American Red Cross, which had only previously admitted white nurses.

Margaret herself a suffragist, was raising money to help rebuild Northern France through CARD, a group co-founded by Anne Morgan. During the war she had been a part of this same group who had driven ambulance, set up medical relief stations, and created “Doughnuts for Doughboys” coffee stands. Back in the U.S., Margaret also set up a hospital in New York for returning soldiers who had been blinded during the war. Here they would learn to read Braille, including the works of fellow Missourian, Mark Twain.

Margaret wintered in New York, a city that fared the pandemic with a much lower death rate than other major U.S. cities. Dr. Royal S. Copeland, a homeopathic physician and the city’s health commissioner enacted the many strict measures that ultimately saw the city through the crisis. Dr. S. Josephine Baker, director of the Department of Health Bureau of Child Hygiene and a leading Progressive reformer, persuaded Copeland to keep the city’s schools open, arguing that kids were safer in school. She knew that, in 1918, of the one million children in NYC public schools, an estimated 750,000 lived in crowded and unsanitary tenement homes. In an article published in the New York Times in November 1918, Copeland said, “[Children] leave their often unsanitary homes for large, clean, airy school buildings.”

Flu ward, 1918. Courtesy of Denver Public Library.

Despite many health warnings and newspaper articles urging quarantine, during the 1918 holidays people must not have stayed home, as by January of 1919 the US was in its third wave of influenza. The virus spread throughout the winter and spring, killing thousands more before subsiding in the summer of 1919, fading away in much the same way the flu ebbs away seasonally. This H1N1 flu continued to circulate seasonally for another 40 years, albeit without the same death toll, until the virus was isolated and vaccines developed. Fast-forward to today, doctors believe that COVID-19 does not have this same seasonal nature and that it will take a vaccine coupled with strict and evenly applied social health measures to recover from this current health crisis.

Ultimately, the 1918 pandemic was devastating, with a loss of life in Colorado at over 8,000 deaths and worldwide at an estimated 50 million, but there was at least one silver lining: It helped elevate women in American society socially and financially, providing them more freedom, employment, independence and a louder voice in the political arena. Today, as we see headlines about inequity and injustice, we ask ourselves, “What would Margaret Brown do?” And we believe that the answer is do your part to take care of one another. Speaking to a reporter in 1914, she said, “I am not taking sides and am here to help all who need aid. I am interested in humanity and will do my duty impartially and conscientiously.”

To learn more about the 1918 Pandemic, visit the CDC’s website. We also recently re-posted a great USA Today article about the holidays and the 1918 pandemic on our Facebook page. Also, check out blogs on the Denver Public Library website, as well as History Colorado for additional information on how Denver responded and recovered 102 years ago. Or, watch this news story featuring Andrea Malcomb, Museum Director: https://denver.cbslocal.com/2020/11/26/2020-covid-thanksgiving-headlines-echo-those-from-1918-spanish-flu-pandemic/

By: Andrea Malcomb, Museum Director